When considering the benefits of a strong United States military, it is natural to think of the military’s crucial role in protecting Americans from foreign adversaries and providing security and stability around the world. But safeguarding America’s interests at home and abroad offers the nation substantial economic advantages as well. Properly understood, the US military offers direct and tangible economic benefits to American businesses, workers, and households.

This chapter discusses some of these benefits. First, I give an overview of some of the ways a strong US military provides support for the structure of the economy by reducing the costs facing businesses, providing a foundation on which global commerce can occur, lowering borrowing costs, and increasing the productivity of private firms and the consumption of households through technological innovation. In certain situations, military spending can also support US businesses and households by smoothing the business cycle. Second, I discuss some conceptual challenges with characterizing the optimal amount of military spending. Though many analysts believe the US should increase defense spending, formulating this need in a rigorous way is difficult. Finally, I discuss the threats to increased defense spending presented by rising interest rates, the deteriorating US fiscal outlook, and weakened—and weakening—international security alliances.

Structural Benefits

A strong and capable military offers many structural features that advance the long-term prosperity of American households and businesses. A comprehensive treatment of those features is beyond the scope of this chapter. Instead, I will focus on four: reductions in costs associated with military protection, the economic benefits of security alliances, the funding advantages enjoyed by military hegemons, and the positive spillovers from investments in military technologies.

Cost Reductions. A strong military reduces the costs facing US businesses, increasing their competitiveness. This can easily be seen by considering naval protection of shipping lanes, which can be viewed as a form of economic technology. Thanks to the protection offered by the US Navy, the costs for private firms to transport goods are much lower than they would be if all shipping convoys had to pay for their own security.

The 2024 Red Sea military conflict illustrates how lawlessness on the high seas can increase the costs facing private businesses. In 2024, the Iran-aligned Houthis damaged more than 40 vessels and targeted nearly five times that number. Attacks continue at the time of this writing (February 2025). The Houthis partly control what cargo enters the Suez Canal, through which 12 percent of global trade flows.1

Higher freight rates and longer shipping journeys added substantial sums to global shipping costs. In fact, the Red Sea attacks appear to have reversed a downward trend in freight rates. The Asia-Mediterranean prices for 40-foot container units were 176 percent higher in January 2024 than five years earlier.2 The price of shipping a container from Shanghai to Rotterdam in July 2024 was five times as high as the average price in 2023.3 Rather than facing the risk of a Houthi attack, many commercial ships avoided the Red Sea altogether and took the longer route around South Africa’s Cape Peninsula, increasing costs.

Insurance premiums for shipments increased as a consequence of the attacks. As of January 2024, roughly two months after the Houthis began attacking merchant vessels, war risk premiums had increased from 0.7 percent of the value of a ship to 1 percent of its value, adding hundreds of thousands of dollars of additional costs for shippers.4

To be clear, I am not asserting a direct link between the US Navy’s capabilities and the Houthi attacks. But this episode is instructive for several reasons. The economic theory of crime argues that the level of criminal behavior increases as the probability of getting away with criminal behavior increases.5 If naval power diminishes, economic theory predicts that more incidents like the Houthi attacks will occur. In addition, the suddenness of the attacks provides a helpful illustration of how quickly and substantially private-sector costs can rise when lawlessness increases. Furthermore, because many of those costs will be passed on to consumers, this episode shows how a strong military can reduce the costs facing households.

Of course, this illustrative example extends beyond naval power. Land-based military strength plays a similar role in providing a foundation on which commerce can take place at relatively lower costs to businesses and households.

Security Alliances. Most of the discussion of political and military alliances like NATO focuses on their diplomatic and security implications. But these alliances have significant economic implications as well. And the strength of NATO is proportional to the strength of the US military. NATO can’t be strong without a strong US military—strengthening NATO is another way in which a strong military advances the economic interests of US businesses and households.

US alliances and forward military presence advance economic outcomes in several ways. They prevent conflict to which the US would be a party. By lowering the odds of US military involvement in a war, they advance the economic interests of American businesses and households. They also deter US adversaries from attacking US allies and deter US allies from instigating military conflict.6 In this way, security alliances and a strong global US military presence help prevent conflicts in other parts of the world that would negatively affect US economic activity.

The degree of economic integration across the world means that US businesses and households are exposed to economic risk from military and security disruptions abroad caused by conflict that does not directly involve America. War abroad can reduce the supply of commodities, increasing their global price. It can hurt US exporters by restricting market access. It can create a chilling effect on US business investment. It can disrupt trade flows and global supply chains, raising costs to US businesses and consumers. And as discussed above, it can increase shipping costs.

By reducing the risk of war and strengthening ties between nations, a strong US military—along with the strong international alliances that a strong US military enables—increases international flows of goods and capital, which boosts American workers’ productivity and wages and US businesses’ competitiveness.7

Trade between the United States and the European Union represents around one-third of global economic output and 30 percent of global trade. Moreover, either the EU or the US is the largest trade and investment partner of nearly every other country in the world.8 Bilateral trade and investment between the EU and US supports 9.4 million jobs (and indirectly supports as many as 16 million jobs). For scale, the number of jobs supported by economic integration is larger than the number of people who live in Switzerland or Virginia.9

European Union companies invest heavily in America. In 2022, they invested €2.7 trillion in the United States.10 These investments increase the stocks of technical knowledge and capital in the US, raising workers’ productivity. Workers that are more productive are more valuable to firms, which go on to compete more aggressively for them in competitive labor markets. This heightened competition puts upward pressure on workers’ wages, increasing household income and potentially increasing employment opportunities and economic output.

Examples from history also help to illustrate this point. A strong US military helped to facilitate Japan’s rapid economic development after the Second World War. Today, Japan is one of America’s strongest economic partners. Japan is a major source of foreign investment in the US and holds more US Treasury securities than any other foreign nation. In 2023, US exports to Japan totaled $121 billion ($77 billion in goods, $44 billion in services). US imports totaled $184 billion, with goods accounting for the majority ($149 billion). In 2021, US-based affiliates of Japanese firms employed nearly one million US workers.11

The United States’ forward military presence has been a major factor contributing to South Korea’s rapid economic development as well. Today, South Korea is one of the largest sources of foreign investment in the United States, with $77 billion of investment in 2023. And US entities find South Korea to be an attractive place to invest. In 2023, the US invested $36 billion in South Korea, which purchased $91 billion of US exports.12

Funding Advantage. Military hegemons enjoy a funding advantage in global debt markets. Investors consider the risk of a hegemon defaulting to be much lower than that of other nations. This credibility with lenders manifests itself in lower interest rates.

The lower interest rates on government debt that exist due to US military hegemony make government borrowing relatively less costly to US taxpayers. Lower rates make it relatively less expensive for businesses to expand operations using debt financing and for households to finance home and auto purchases.

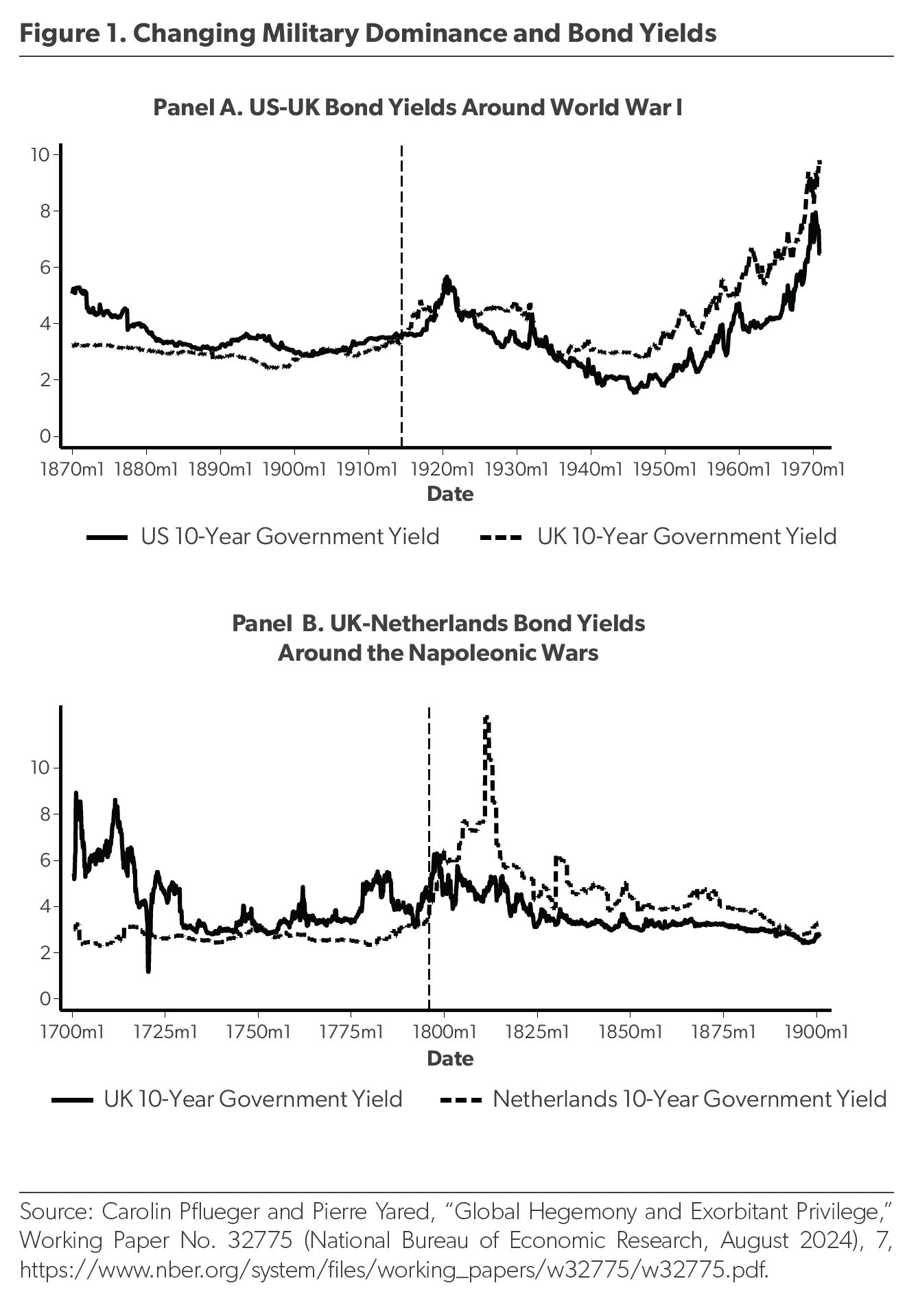

To demonstrate the funding advantage of military hegemons, economists Carolin Pflueger and Pierre Yared study the interest rates on government debt around the time of hegemonic transitions. Specifically, they study the transition in hegemonic regimes from Great Britain to the United States in the period spanning the First and Second World Wars and the transition at the end of the 18th century from the Netherlands to Great Britain.13

As Figure 1, Panel A shows, before World War I, Britain was able to borrow at cheaper rates than the US was. This reversed after that war. Following World War II, the United States’ funding advantage was solidified. Similarly, the Dutch navy was dominant in the 16th through 18th centuries. But the Netherlands was invaded by the Napoleonic armies in 1795, after which it lost its funding advantage over Britain (Figure 1, Panel B).

Pflueger and Yared also find that the funding advantage enjoyed by a hegemon increases as the risk of military conflict increases. Moreover, the hegemon’s funding advantage may increase even if the conflict does not directly involve the hegemon. In Figure 2, Pflueger and Yared demonstrate that the United States’ funding advantage relative to both Russia and Ukraine increased following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Technology Spillovers. Military technology can have important spillovers into the private sector, generating economic value for US businesses and households.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is the best example of this. Following the 1957 launch of Sputnik, DARPA was created by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to ensure US military superiority in America’s competition with the Soviet Union. DARPA awards research and development (R&D) grants to researchers at universities and private companies. Scientists insulated from politics make the grant decisions, with the goal of funding high-risk, high-reward projects.

DARPA has made material contributions to a large number of technological breakthroughs in recent decades, including weather satellites, materials science, the computer mouse, the internet, miniaturized GPS receivers, high-definition TV, wafer-scale semiconductor integration, and autonomous vehicles, among many others.14

To be sure, following a 1973 amendment to its mission, the purpose of DARPA is not to create commercial technology. But, as the list above demonstrates, its military projects have commercial spillovers.

A potential concern may be that an expansion of government-funded R&D might crowd out private R&D. This might happen if the supply of research inputs in an economy is limited and nonresponsive to an increase in research resources (e.g., if there are only so many scientists in a particular industry).15 In this case, government R&D funding merely shifts research activity away from projects prioritized by the private sector and toward projects prioritized by the government.

At the same time, it is also possible that public-funded R&D might crowd in private R&D (i.e., that an increase in government funding for research might stimulate additional private-sector research). Public research might fund large fixed costs (e.g., labs and human capital accumulation), which might make private projects feasible on the margin. Technological and human capital spillovers across firms are another reason to suspect that crowding in could occur.16

In a recent paper, economists Enrico Moretti, Claudia Steinwender, and John Van Reenen use a country-industry-year-level dataset for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries and a firm-year-level dataset for France to study this question. They focus on defense-related R&D spending.17

They find strong evidence of crowding in. In their preferred estimates, a 10 percent increase in defense R&D translates into a 5 percent increase in privately funded R&D. In 2002, government-funded aerospace R&D was $3 billion. According to their estimates, this generated an additional $1.9 billion in privately funded aerospace R&D. Their results imply that government R&D spending generates twice as much private-sector R&D spending as R&D tax credits. They also find that defense R&D increases overall productivity growth and economic growth, albeit modestly.18

The US should not fund defense research with the goal of creating commercial spillovers. But when such spillovers occur, they can create wealth for US households that can be well in excess of the level of their congressional appropriation.

Short-Term Economic Benefits

In the previous section, I discussed some of the long-term, structural benefits of a strong US military for the nation’s economy, businesses, and households. There may be short-term benefits as well. This is particularly true during economic downturns, when consumers and businesses pull back on spending. In a recession, there is a compelling case for increased government spending to offset those private-sector declines.

Proponents of this sort of Keynesian response to recessions often overstate their case. Government spending can stabilize overall economic output during a recession, but it cannot permanently increase output. It boosts output today, but it has future offsetting effects from the economic drag of additional debt, consequent inflationary pressures, the response of monetary policy, or other factors. (If this weren’t the case, then policymakers should stimulate the economy at all times.)

These considerations have important implications for the design of economic stimulus—namely, that the timing and composition of the government stimulus spending matters.

Defense outlays are attractive due to the ability of policymakers to time them appropriately. Stimulus spending that relies on infrastructure investment often gets the timing wrong because there are not many “shovel-ready jobs” when the economy is contracting and the permitting process for such projects is onerous and long. Similarly, stimulus in the form of temporary tax cuts or direct checks to households suffers from a timing problem because policymakers are not able to control when households actually spend the money they receive. But Congress can quickly increase appropriations for the Department of Defense, which can in turn quickly spend appropriated funds.

Regarding composition, defense spending is an attractive option for stimulus because, unlike make-work infrastructure projects with low social value or stimulus checks to high-income households, it is not wasteful. The Department of Defense should spend on items during the recession that it would eventually have to purchase in the future, essentially pulling forward future spending into the period of economic slack.

That spending should include an increase in outlays for procurement, research, and operations and maintenance, which would boost the economy when private spending is falling. In a severe recession with rising long-term unemployment, the spending could potentially include an increase in recruitment as well.

Of course, even during a severe recession, it is important for Congress to scale the size of any stimulus package to the underlying economic need. The importance of this observation—well-grounded in economic theory and evidence—was apparent in the aftermath of the American Rescue Plan of 2021. According to my calculations, by stimulating demand well in excess of the economy’s underlying productive capacity, the American Rescue Plan contributed 3 percentage points to underlying inflation in 2021.19

In a mild economic downturn, it is typically prudent to leave business cycle management to the Federal Reserve. That is true for several reasons, including that it is difficult to temporarily increase military spending (and hiring). The basic idea is to pull future spending into the present—an idea that is prudently applied only to severe downturns that are relatively long-lived. But in such a severe recession—like the US experienced following the 2008 global financial crisis—there is a clear role for fiscal policy. Temporary increases in defense spending offer a particularly attractive form of economic stimulus.20

Optimal Defense Spending

Economists might naturally wish to characterize the optimal level of defense spending. This is a challenging exercise.

Marginal Analysis and Insurance. In determining the optimal level of defense spending, economists might naturally reach for a notion of costs and benefits, arguing that the optimal amount of defense spending is the amount at which the marginal benefit of the last dollar of defense outlays equals its marginal cost. The basic intuition: If the benefit of additional spending is greater than the cost, then the government should increase spending, and if the benefit of additional spending is less than the cost, then the government should reduce spending; therefore, the optimum occurs at the spending level when the benefit and cost of the marginal dollar of expenditure are equal.

The challenge with this approach is that, while the costs of defense outlays are clearly defined, the benefits are not. How to quantify the economic benefit of a major war that never happened?

Economists might also consider defense spending as a form of insurance. To see this intuition, consider a simple descriptive illustration. Suppose there are two states of the world, one in which the US has a strong military and one in which the US has a weak military. Think of defense spending as insurance against a major economic contraction brought on by military conflict that directly involves either the US or a US trading partner.21 Unlike a typical insurance policy, national defense cannot be turned on and off on an annual basis, so in this descriptive illustration defense spending happens in all periods.

To fully insure, the US should spend on defense an amount equal to the product of the probability of a major contraction caused by conflict, the amount of national income lost in such an event, and the frequency of such events. Assume that, with a weak military, the odds in any given year of such a conflict are 10 percent. In this case, relative to current defense outlays, the US is underinvesting in defense when the fourth such event occurs. Assume that, with a strong military, the odds are 2 percent. In this case—again, relative to current defense outlays—the US is underinvesting in defense when the 19th such event occurs.22

And, of course, viewed as a form of insurance, defense outlays mitigate risk from not just disasters but also a host of economic disruptions, such as those discussed in the structural benefits section above.

Share of Gross Domestic Product Target. Many foreign policy scholars and advocates of increased defense spending argue for spending a certain share of national income on defense (e.g., 5 percent). A target of 5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) is a useful framework in the current policy debate because it implies a substantial but politically and economically achievable increase in defense outlays.

However, a share-of-GDP framework would imply that defense spending should fall when the economy contracts. As I argued previously, if anything, defense spending should increase in a recession.

Moreover, it is likely the case that—over a sufficiently long time horizon—national income and the nation’s defense needs do not increase one for one. A 10 percent increase in national income does not necessarily imply that the US needs 10 percent more aircraft carriers or soldiers. Historically, surplus income gains have flown disproportionately away from necessities. For example, as the US became wealthier, the share of national income spent on food fell from 15.7 percent in 1929 to 10 percent in 1970 to 5.3 percent in 2012.23

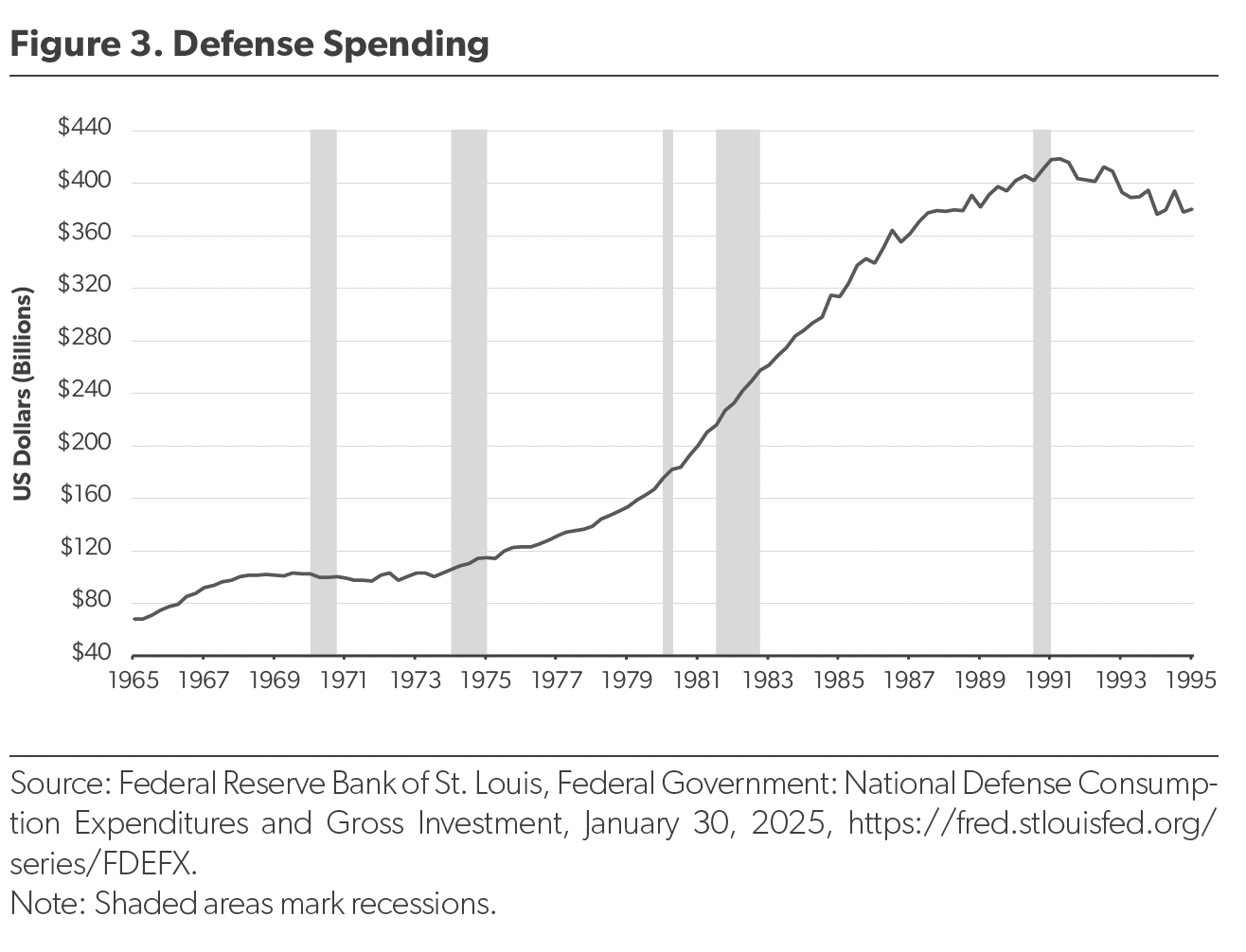

Strategic Competition. As shown in Figure 3, President Ronald Reagan increased defense spending by 57 percent between 1981 and 1985 in order to win the arms race with the Soviet Union. Analogously, the US might characterize its optimal defense spending as a target relative to China’s defense spending—say, 180 percent of Chinese spending,24 or the growth rate of China’s spending plus a markup.

Three Challenges to Increasing Military Spending

There are at least three major challenges advocates of increased defense spending need to address: a higher neutral rate of interest, the US fiscal outlook, and President Donald Trump’s efforts to weaken international security alliances.

Rising Neutral Interest Rate. Higher interest rates are a major challenge for defense spending when that spending is financed by government borrowing because the level of interest payments on the debt rises with borrowing rates. It appears that higher interest rates will be a feature of the US economy, at least over the medium term, making their challenge to the goal of increasing defense outlays greater.

Interest rates started increasing in the early months of 2022, as the Federal Reserve began its efforts to control rapidly rising consumer prices. But the inflation of 2021 is not the only reason interest rates are increasing.

The principal determinant of interest rates is the balance between the demand for investment and the supply of savings. In recent years, many factors affecting investment and savings have led to considerable upward pressure on interest rates. Elevated geopolitical tensions are leading to rising military spending, which, along with a greater reliance on deficit financing, is pushing up debt levels. Elevated tensions are also leading some supply chains to reorganize. So-called resiliency investments are becoming more common. Investment demand is elevated due to the energy transition and the prospect that advances in artificial intelligence will increase productivity growth and the profitability of certain businesses.

The neutral rate of interest is the rate that prevails when the economy is at full employment and inflation is at the Federal Reserve’s target. Since the end of 2019, the median view among voting members of the Fed’s policy-setting committee was that the neutral overnight interest rate was 2.5 percent. Last year, this view began to shift upward. In December 2024, the median Fed member thought this neutral rate was 3 percent.25 In my view, the actual neutral rate is at least 4 percent.

Accordingly, longer-term interest rates—which matter most for investment decisions—are rising. The yield on a 10-year Treasury bond was around 2 percent before the pandemic. At the time of this writing (February 2025), it is 4.6 percent.

Economists debate whether interest rates—particularly longer-term rates—will remain high over the coming years.26 To the extent that they do, they present a challenge to efforts to increase defense spending.

Fiscal Outlook. Similarly, the US fiscal outlook will make it challenging for Congress to increase military outlays.

Over the half century from 1975 to 2024, the average annual federal budget deficit was 3.8 percent of GDP. The deficit in 2024 pulled up that average: It was an eye-popping $1.9 trillion, or 6.6 percent of GDP. In 2035, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office expects the deficit to be 6.1 percent of that year’s economic output. Moreover, in 2025, Congress is likely to change federal tax law in a way that will increase deficits above these projections.

Over the next decade, the Congressional Budget Office expects three categories of spending to increase: Social Security, Medicare, and interest payments on the national debt. Other government spending (e.g., defense, education, law enforcement, disaster relief, and national parks) is projected to fall as a share of annual economic output.27

Rising spending on these programs crowds out fiscal and political space to increase defense spending. Congress and Trump would do well to consider the warning issued in 2011 by Admiral Michael Mullen, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff:

I believe that our debt is the greatest threat to our national security. If we as a country do not address our fiscal imbalances in the near-term, our national power will erode. Our ability to respond to crises and to maintain and sustain influence will diminish.28

The national debt’s share of GDP has increased by 61 percent since Admiral Mullen’s warning.

Weakening Security Alliances. Throughout the past eight years, Trump has shown considerably less support for NATO than his predecessors did. This has been true with respect to Trump’s rhetoric, but also his actions.

In his first term, Trump increased tariff barriers on imported goods from key security allies, including European nations and Canada. Joe Biden followed suit, with industrial subsidies that tilted the playing field toward the US so dramatically that they led to French President Emmanuel Macron warning they could “fragment the West.”29 And since taking office for his second term, Trump has again threatened Europe with additional tariffs and increased tariff rates on Canada (along with Mexico and China). Moreover, at the time of this writing (February 2025), Trump and senior members of his administration have actively sought to distance the US from European allies with respect to the war in Ukraine, the threat to Europe posed by Russia, and the rise of extremist political parties in some European nations.

One of the ways a strong US military increases the prosperity of American businesses and households is strengthening the security alliances that have been a bedrock of prosperity since the end of the Second World War. By weakening those alliances, Trump is weakening the economic return on taxpayer dollars invested in defense outlays.

In January 2025, Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, warned that the world economy has “started fracturing along new lines” after Trump threatened to increase tariffs. She warned that it was in “no-one’s interest, to break the bonds in the global economy.”30

Scholars and advocates usually, and correctly, think of the domestic economic benefits from international alliances as being downstream from the security benefits. But stronger economic benefits with allied nations can increase the value of alliances. And weaker economic relationships make such alliances less valuable.

Conclusion

A strong military costs money. At a time of rising deficits and growing debt, it is tempting to consider reducing defense outlays. I am an economist, not an expert in defense or foreign affairs—but just as you don’t need to be a meteorologist to know it’s raining, it is apparent that land wars in Europe and the Middle East and rising geopolitical tensions in the south Pacific require a stronger US military. From a security perspective, now is not the time to cut defense spending. Military outlays should increase above current levels.

As this chapter has demonstrated, a stronger military will also advance long-term prosperity, strengthening the economic outcomes of businesses, workers, and households. Taxpayers spend large sums on defense. But they get a high return on their tax dollars.

Notes

- Andres B. Schwarzenberg, Red Sea Shipping Disruptions: Estimating Economic Effects, Congressional Research Service, May 8, 2024, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12657

- World Trade Organization, Global Trade Outlook and Statistics, April 2024, https://www.wto-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789287076335/read

- The Economist, “Inside the Houthis’ Moneymaking Machine,” January 18, 2025, https://www.economist.com/interactive/international/2025/01/18/inside-the-houthis-moneymaking-machine

- Jonathan Saul, “Red Sea War Insurance Rises with More Ships in Firing Line,” Reuters, January 16, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/red-sea-war-insurance-rises-with-more-ships-firing-line-2024-01-16/

- See, for example, Gary S. Becker, “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach,” Journal of Political Economy 76, no. 2 (1968): 169–217, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/259394

- Hal Brands and Peter D. Feaver, “What Are America’s Alliances Good For?,” Parameters 47, no. 2 (2017): 15–30, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2928&context=parameters

- See, for example, Vincenzo Bove et al., “US Security Strategy and the Gains from Bilateral Trade,” Review of International Economics 22, no. 5 (2014): 863–85, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/roie.12141

- European Commission, “EU Position in World Trade,” https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/eu-position-world-trade_en; Central Intelligence Agency, “The World Factbook: Field Listing—Imports—Partners,” https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/imports-partners/; and Central Intelligence Agency, “The World Factbook: Field Listing—Exports—Partners,” https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/exports-partners/

- European Commission, “EU Trade Relations with the United States. Facts, Figures and Latest Developments.,” https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/united-states_en

- European Commission, “EU Trade Relations with the United States.”

- Cathleen D. Cimino-Isaacs and Kyla H. Kitamura, U.S.-Japan Trade Agreements and Negotiations, Congressional Research Service, April 3, 2024, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11120

- Liana Wong and Mark E. Manyin, U.S.-South Korea (KORUS) FTA and Bilateral Trade Relations, Congressional Research Service, November 19, 2024, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10733

- Carolin Pflueger and Pierre Yared, “Global Hegemony and Exorbitant Privilege,” Working Paper No. 32775 (National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2024), https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w32775/w32775.pdf

- Michael R. Strain, “Protectionism Is Failing and Wrongheaded: An Evaluation of the Post-2017 Shift Toward Trade Wars and Industrial Policy,” in Strengthening America’s Economic Dynamism, ed. Melissa S. Kearney and Luke Pardue (Aspen Institute, 2024), https://www.economicstrategygroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Strain-AESG-2024.pdf

- Austan Goolsbee, “Does Government R&D Policy Mainly Benefit Scientists and Engineers?,” Working Paper No. 6532 (National Bureau of Economic Research, April 1998), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=226269

- Enrico Moretti, “Workers’ Education, Spillovers, and Productivity: Evidence from Plant-Level Production Functions,” American Economic Review 94, no. 3 (2004): 656–90, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/0002828041464623

- Enrico Moretti et al., “The Intellectual Spoils of War? Defense R&D, Productivity, and International Spillovers,” Review of Economics and Statistics 107, no. 1 (2025): 14–27, https://eml.berkeley.edu/~moretti/military.pdf

- Moretti et al., “The Intellectual Spoils of War?”

- Michael R. Strain, “Yes, the Biden Stimulus Made Inflation Worse,” National Review, February 10, 2022, https://www.nationalreview.com/corner/yes-the-biden-stimulus-made-inflation-worse/; and Michael R. Strain, “The American Rescue Plan: Some Good, Some Bad and Too Large,” testimony before the House Committee on Financial Services, February 4, 2021, https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/2021.02.04_biden.stimulus.testimony.pdf?x85095

- Some economists believe government spending is relatively more stimulative when the unemployment rate is high or when policy interest rates are very low and relatively less stimulative in the presence of high government debt. For a review of this literature and discussion of these issues, see Valerie A. Ramey, “Ten Years After the Financial Crisis: What Have We Learned from the Renaissance in Fiscal Research?,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33, no. 2 (2019): 89–114, https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.33.2.89

- Such events do happen, and not just due to war. Studying 36 countries with data beginning between 1870 and 1914 and ending in 2006, economists Robert J. Barro and Tao Jin calculate that the probability of a macroeconomic disaster in which GDP contracts by at least 10 percent is 0.04, that the US experienced five such disasters in the first half of the 20th century, and that the average magnitude of a disaster is the loss of 20 percent of GDP. See Robert J. Barro and Tao Jin, “On the Size Distribution of Macroeconomic Disasters,” Econometrica 79, no. 5 (2011): 1567–89, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41237785.pdf

- Unlike a typical insurance setting, a nation can’t buy and cancel the existence of a military in the same way a person can buy and cancel an insurance policy. So in this illustration, military spending occurs every year. Now, I’ll define some terms. Defense spending (defined here as outlays as a share of annual GDP) is d. The probability of a catastrophe is p. The loss in the event of a catastrophe is L. The number of catastrophes is n. In this simple illustration, the US is underinvesting in defense spending if d

d ∕ (p × L). At the time of this writing, d = 0.037. We are assuming that a catastrophe results in GDP contracting by 10 percent, or L = 0.1. With a probability of catastrophe of 0.1, the US is underinvesting when the fourth catastrophe occurs; with p = 0.02, when the 19th event occurs.

- For more discussion of this issue, see Michael R. Strain and Alan D. Viard, “Six Long-Run Tax and Budget Realities,” Tax Notes 139, no. 13 (2013), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2233953

- The precise amount China spends on its military is hard to determine. Mackenzie Eaglen argues that in 2022, China spent roughly the same as the US. Using Eaglen’s numbers, if the US had spent 5 percent of GDP on defense in 2022, it would have spent 180 percent more than China on defense. Mackenzie Eaglen, Keeping Up with the Pacing Threat: Unveiling the True Size of Beijing’s Military Spending, American Enterprise Institute, April 29, 2024, https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/keeping-up-with-the-pacing-threat-unveiling-the-true-size-of-beijings-military-spending/

- Federal Reserve, Federal Open Market Committee, “Meeting Calendars, Statements, and Minutes (2020–2026),” https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomccalendars.htm

- See, for example, Olivier Blanchard, “Secular Stagnation Is Not Over,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, January 24, 2023, https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2023/secular-stagnation-not-over

- Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035, January 2025, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61172

- Michael G. Mullen, testimony before the Senate Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Defense, June 15, 2011, https://ogc.osd.mil/Portals/99/testMullen06152011.pdf

- Yasmeen Abutaleb et al., “Biden Says He Might Meet with Putin—but Not Now,” The Washington Post, December 1, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/12/01/macron-biden-warning-western-alliance/

- Ursula von der Leyen, “Davos 2025: Special Address by Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission,” January 21, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/01/davos-2025-special-address-by-ursela-von-der-leyen-president-of-the-european-commission/