A constant concern in national security is the alignment between strategy and budget—whether the resources available are necessary and sufficient to support the force structure and capabilities the strategy demands. This concern is especially relevant in the current fiscal environment. The overall federal budget deficit is projected to exceed $1.9 trillion in fiscal year (FY) 2025 and grow to more than $2.8 trillion by FY2033. The debt held by the public now exceeds the size of the economy, and the nation spends more on interest payments than national defense.1

The deteriorating global security environment makes the situation even more alarming. A revanchist Russia is at war in Europe, an increasingly coercive China is attempting to shift the balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region, the rogue states of Iran and North Korea are more emboldened and enabled through their ties with Russia and China, and terrorist organizations, such as Hamas and Hezbollah, are waging proxy wars on behalf of their sponsors.

The tension between fiscal and security concerns is not new. In the early years of the Cold War, the nation faced the dual dilemmas of rising deficits and growing threats. In National Security Council (NSC) policy paper 162/2, the Eisenhower administration acknowledged this tension, noting that “it is vital that the support of defense expenditures should not seriously impair the basic soundness of the U.S. economy.”2 The strategist Bernard Brodie observed in 1959 that “today we are spending far more on security than we have ever spent before in peacetime, but we are fated to remain far less secure.” He went on to write that the nation’s security needs are “essentially limitless,” while the resources available for defense are “definitely limited.”3 Defense could always benefit from more funding because the nation can never be too secure, but the nation does not have an unlimited ability to spend.

When Robert McNamara took over the Pentagon in the 1960s, the “Whiz Kids” he brought into government reframed the problem with a deceptively simple question: How much is enough?4 Their concerns were primarily about sufficiency and efficiency: How much is necessary to meet the threats the nation faces at an acceptable level of risk? Implicit in this question is the assumption that a sufficient level of defense spending—a budgetary floor for what is necessary—is also an affordable and prudent level of spending.

The threat environment today is arguably more complex than it was during the Cold War, and the decline of the nation’s overall fiscal health further complicates the situation. These factors have morphed the debate over defense spending into a debate over affordability. Is defense spending harming the nation’s fiscal health and economic security? Is defense spending on an unsustainable trajectory? What can the nation really afford to spend on defense? These questions imply a theoretical maximum level of spending—a budgetary ceiling for what is affordable and sustainable. Rather than asking how much is enough, policymakers are increasingly asking, How much is too much?

The fear is that the two trend lines—how much is enough and how much is too much—have crossed and the nation can no longer afford to execute its current strategy. If this is true, critics argue, a new and more restrained strategy is required—one that reduces America’s role in the world and the military’s role in US foreign policy.5 The economic and security consequences of such a shift in strategy would be profound.

Rather than assuming the worst, this chapter seeks to answer the question of how much is too much by looking at quantitative trends in the budget, the economy, and other nations’ defense spending to determine what characteristics are associated with an unaffordable and unsustainable level of US defense spending. It explores trends in defense spending adjusted for inflation, as a share of the federal budget, compared with other nations, and as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). It concludes with an assessment of what each of these indicators suggests about the affordability of current and proposed levels of defense spending.

Defense Spending in Inflation-Adjusted Dollars

From the founding of the nation through the end of World War II, US defense spending followed a predictable pattern. In times of peace, the United States maintained a minimal military force with minimal funding. When war approached, the nation quickly mobilized forces and increased spending. And each time war subsided, it demobilized forces and returned to a minimal state of funding.6 The advantage of this approach is that it required much less funding during peacetime. The disadvantage, however, was that the nation often found itself unprepared at the outset of conflict with insufficient time to mobilize. While the United States arguably won every war during this period, it was not without false starts and unnecessary loss of life.7

This pattern of rapid mobilization and demobilization ended with the start of the Cold War. A new trend emerged that was less a strategic choice than a consequence of changes in the conduct of war. The combination of nuclear weapons, long-range missiles and bombers, and a long-term strategic competition with the Soviet Union meant the US military could no longer rely on its ability to mobilize. Intercontinental-range weapons negated the US geographic advantage of having large oceans to its east and west and compliant neighbors to its north and south. The nation could find itself at war with little warning, and the military had to be ready to fight at a moment’s notice.

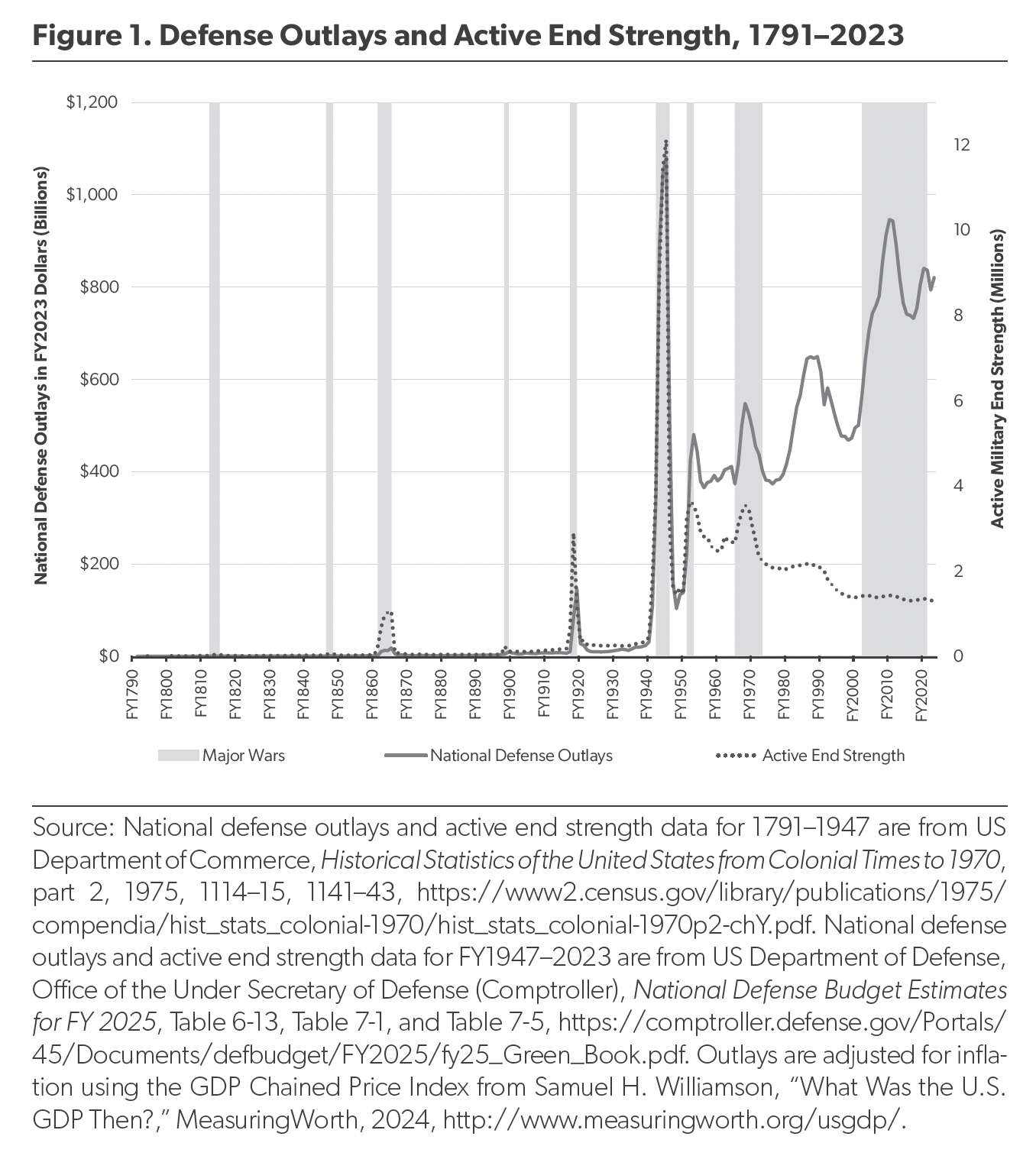

Figure 1 shows total defense outlays (adjusted for inflation) versus active end strength (i.e., the number of people in the active-duty military at the end of each fiscal year). After World War II, the two trend lines diverged at a pace not previously seen. While the overall budget continued to rise and fall in cycles corresponding to the Korean War, Vietnam War, military buildup of the 1980s, and wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the gap between defense spending and force size continued to grow. The trend is similar with other measures of force size, such as the number of ships in the Navy or combat aircraft in the Air Force.8

These trends highlight a core structural issue in the defense budget. Since FY1950, the total cost per person (including compensation, operations, equipment, basing, and all other costs) has grown at a compound annual rate of 2.7 percent above inflation, a rate that is remarkably similar to what military and civilian leaders have called for in recent years. For example, in a 2017 congressional testimony, General Joseph Dunford, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, stated, “We know now that continued growth of the base budget of at least 3 percent above inflation is the floor necessary to preserve today’s relative competitive advantage.”9

Growth in the cost per person above inflation is due to three main factors. First, the Department of Defense’s labor costs—particularly the costs of military compensation and benefits, including health care—have grown faster than inflation. This trend accelerated during the 2000s, but in recent years it has moderated.10 The costs of operating and maintaining major weapons systems, such as aircraft, ships, and ground vehicles, have also grown as these platforms have aged. And as these legacy systems are replaced, the latest generation of weapons systems often cost even more to operate and maintain.11 Finally, the threats our military faces and the pace of innovation required to meet these threats is accelerating, requiring higher levels of research and development just to keep pace with threats and progressively higher unit costs to procure more advanced weapons.12 These trends suggest, as General Dunford and others have asserted, that to sustain the same size force at roughly the current level of readiness with modernization programs that merely keep pace with threats will require a budget that grows at about 2.7 percent above inflation.

Growth in the cost per person above inflation is concerning, but it appears to be largely unavoidable, notwithstanding a significant reduction in threats or a change in the political constraints placed on how defense funding is allocated.13 Whether this trend is affordable in the long term depends on whether the cost per person grows faster than the economy. Over time, this would mean that either the size of the military must get progressively smaller or the nation will need to devote a progressively larger share of the economy to defense. While this could be tolerated in the short term, in the long term it would eventually be unsustainable because either the military would become too small to do anything meaningful or its budget would consume an ever-increasing share of the economy.

Thankfully, this is not the situation the United States finds itself in today. From 1950 through 2023, the US economy grew at a compound annual rate of 3.1 percent in real terms.14 While the economy has its ups and downs, as long as the long-term rate of growth in the defense budget’s cost per person remains below the long-term rate of economic growth, the current trajectory is sustainable. Despite claims to the contrary, the mere fact that total defense spending and the cost per person are growing faster than inflation does not mean the current trajectory is unaffordable or unsustainable.15

Defense Spending as a Share of the Federal Budget

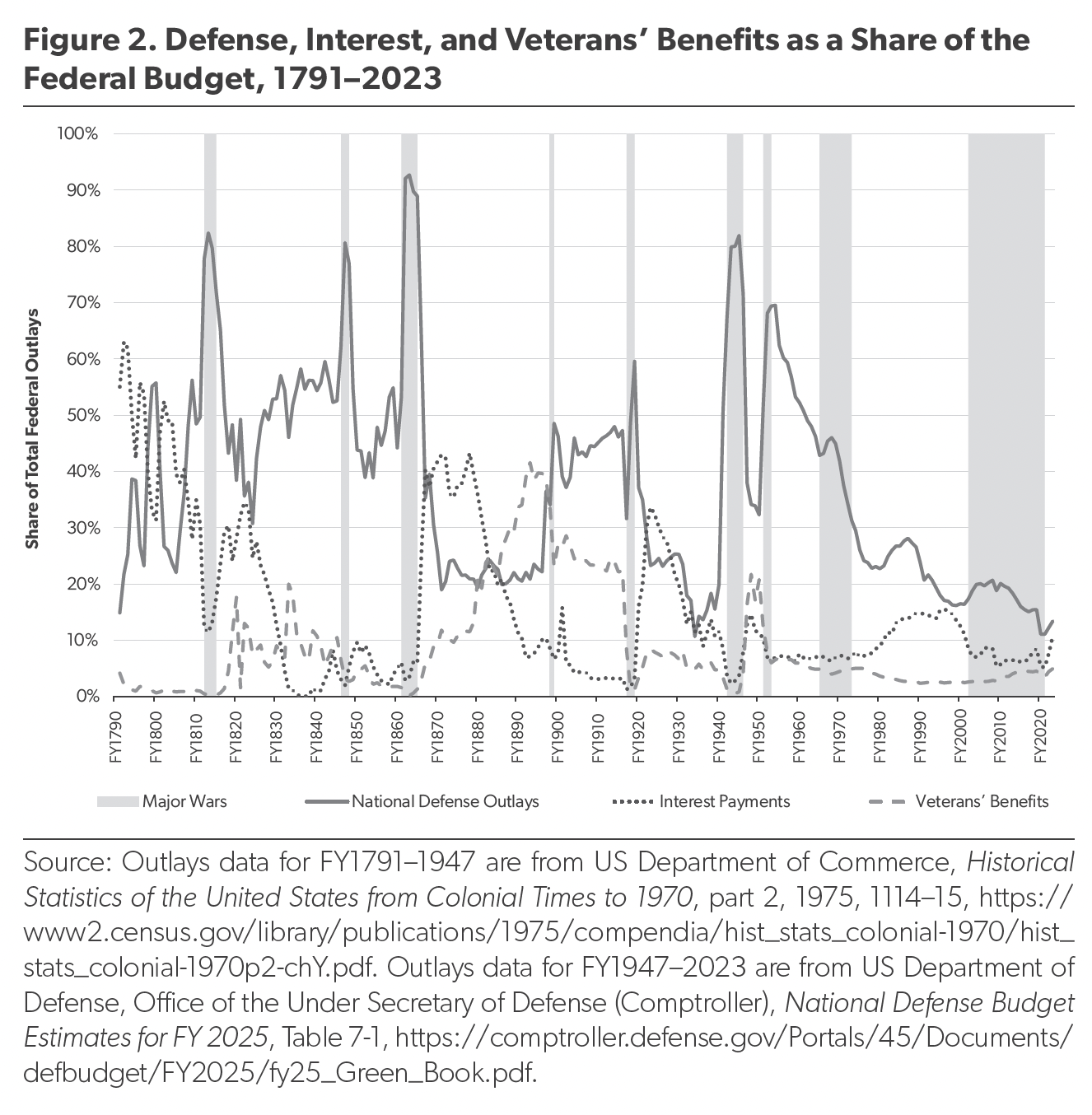

Another metric often cited in debates over affordability is the share of the overall federal budget used for defense. As shown in Figure 2, the share of the budget allocated for defense has varied considerably over time, particularly during times of war. From 1791 to just before the Civil War (1860), defense consumed an average of 45 percent of the federal budget (excluding the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War). In contrast, from the post–Civil War era to just before the Spanish-American War (1867–97), defense consumed just 24 percent of the overall budget. This decrease was due in part to higher levels of spending in other parts of the government, particularly interest payments on the public debt and the cost of veterans’ benefits. In FY1871, for example, the nation spent $126 million on interest and $34 million for veterans’ benefits, compared to $36 million for the Army and $19 million for the Navy. For nearly every year from 1791 through 1930, these three areas of the federal budget (i.e., defense, veterans’ benefits, and interest) together consumed more than half the federal budget.

In the 1930s, the composition of the federal budget began to change in significant ways, and defense fell as a share of overall federal spending. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal led to a sharp increase in nondefense spending for new programs, such as Social Security, and efforts to pull the country out of the Great Depression. These trends temporarily reversed during World War II, with defense surging to more than 80 percent of the overall federal budget, as it had during the War of 1812, Civil War, and Mexican-American War. After the war, however, the increases in nondefense spending that began under Roosevelt continued.

On the surface, the trends in Figures 1 and 2 may seem in conflict with one another because Figure 1 shows a general increase in defense over the past seven decades, while Figure 2 shows a general decline. Both are true because they measure different things. Since the end of World War II, defense spending grew faster than inflation, but nondefense spending grew at an even faster rate, causing defense as a share of the overall budget to decline.

This suggests that the United States could spend a much greater share of its budget on defense, as it has in the past. The nation spends a smaller share on defense because other forms of spending have taken priority. This is a policy choice, but it is not a fiscal constraint.

US Defense Spending Compared with Other Nations

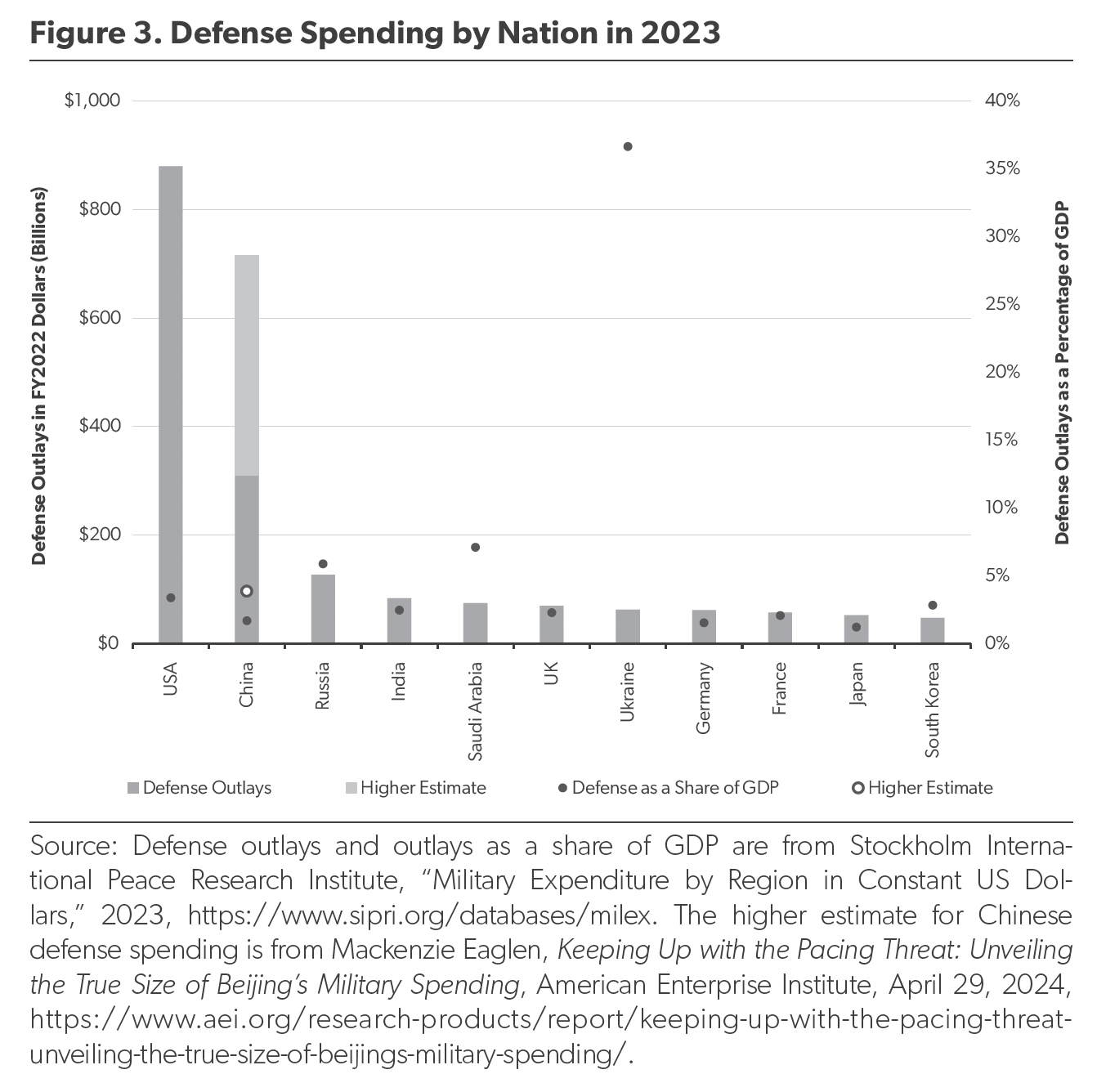

The debate over the level of defense spending often references how much the United States spends on defense relative to other nations. Such a comparison, however, is difficult to make because we do not always know with accuracy what other nations spend on defense, labor and material costs vary significantly among nations, and the way countries categorize defense and nondefense spending varies. As shown in Figure 3, estimates for China’s defense spending range from $309 billion to $711 billion (in 2022 US dollars).16 Although China is quickly catching up, the United States still spends more than any other nation on defense. As a share of GDP, though, the United States spends less than many other nations—Ukraine, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and others devote much more of their economy to defense.

These comparisons do little to shed light on whether the United States is spending too much. The United States spends more than other nations because it has more security commitments around the world—it is the primary defender of the global economic system and the free flow of commerce that enables our modern way of life. While this may not seem fair, and allied nations could certainly spend more, the United States spends the most because it has the most at stake. This does not mean the United States is spending too much or more than it can afford—it merely means it is spending more than others.

Defense Spending as a Share of GDP

Defense spending as a share of GDP is a measure commonly used to argue that the nation can or should spend more on defense. Some proponents of higher spending point to the general decline over the past seven decades, shown in Figure 4, as evidence that defense spending is on the decline. However, as Figure 1 made clear, defense spending has not actually declined—it is near a post–World War II high in inflation-adjusted dollars. This common misunderstanding stems from the fact that defense spending as a share of GDP (Figure 4) is the ratio between two weakly correlated values: defense outlays in the numerator and the size of the overall economy (GDP) in the denominator. These values are weakly correlated because they can move in opposite directions. When the economy contracts during a recession, defense spending can increase; when the economy is expanding, defense spending can decline.

Defense spending as a share of GDP is different from defense spending. Defense spending as a share of GDP measures the economic burden of defense—how much of the nation’s economy is used each year to provide for the common defense. Because it is a ratio of two values, it rises and falls in response to changes in both the numerator and the denominator, which can be counterintuitive. If defense spending grows and GDP grows even faster, the ratio becomes smaller. Likewise, if defense spending declines and GDP declines even faster, the ratio becomes larger. In 2020, for example, Japanese defense spending fell by 1.2 percent (or 0.9 percent adjusting for inflation) from the prior year, but defense spending as a percentage of GDP grew from 0.99 percent to 1.02 percent. Japan spent less on defense, but because its economy contracted by even more, defense as a percentage of GDP went up.17

Attempting to peg the defense budget to a certain share of the economy or use the percentage of GDP as a floor for defense spending is fundamentally unsound. In the case of Japan in 2020, holding defense as a share of GDP steady would have meant even deeper cuts in defense spending. The United States has never stayed at a relatively stable level of defense spending, either in inflation-adjusted dollars or as a share of the economy, because world events have a way of intervening. It stands to reason that defense spending should rise and fall based on changes in strategy and threats. Defense spending should not be dictated by economic activity or the whims of the business cycle that drive GDP growth. Setting spending at a fixed level of GDP lets the budget drive the strategy rather than letting strategy drive the budget; it is based on the nation’s ability to spend rather than what it needs to spend.

While the economic burden of defense is not a useful indicator of whether the nation is spending enough on defense, it is perhaps an ideal measure of whether the nation is spending too much. Defense as a share of GDP is best used as a ceiling for defense spending rather than a floor. If the economic burden of defense is too high, it could hamper economic growth and lead to a downward and self-reinforcing economic spiral, as the Eisenhower administration warned about in NSC 162/2. There is no such economic risk from having too low of a defense burden, but there is surely a security risk from having too low of an absolute level of defense spending (regardless of GDP).

History serves as a useful guide for how large a defense burden the economy can support—a theoretical ceiling. The United States has only spent more than 10 percent of GDP on defense four times in its history, and each time was relatively short in duration and in support of major wars. Some Middle Eastern nations, such as Israel, Jordan, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, have spent well above 10 percent of GDP for many years consecutively. Israel, for example, spent more than 20 percent of GDP on defense from 1970 through 1978—a period in which it faced significant security challenges.18 Ukraine currently spends more than 30 percent of GDP on defense, similar to the United States during World War II. As a general rule of thumb, however, spending more than about 10 percent of GDP on defense should be reserved for the direst circumstances.

In peacetime, one expects that the threshold would be lower. From the end of the Korean War through the end of the Cold War (FY1954–90), the United States averaged spending 6.6 percent of GDP on defense, and during this time the economy grew at a compound annual rate of 3.5 percent above inflation. From FY1991 through FY2023, the nation spent an average of 3.2 percent of GDP on defense, and the economy grew at a compound annual rate of 2.6 percent above inflation.19 To be clear, this correlation does not necessarily mean that higher defense spending causes higher economic growth, but it does suggest that spending more than 6 percent of GDP on defense did not harm the economy in the past.

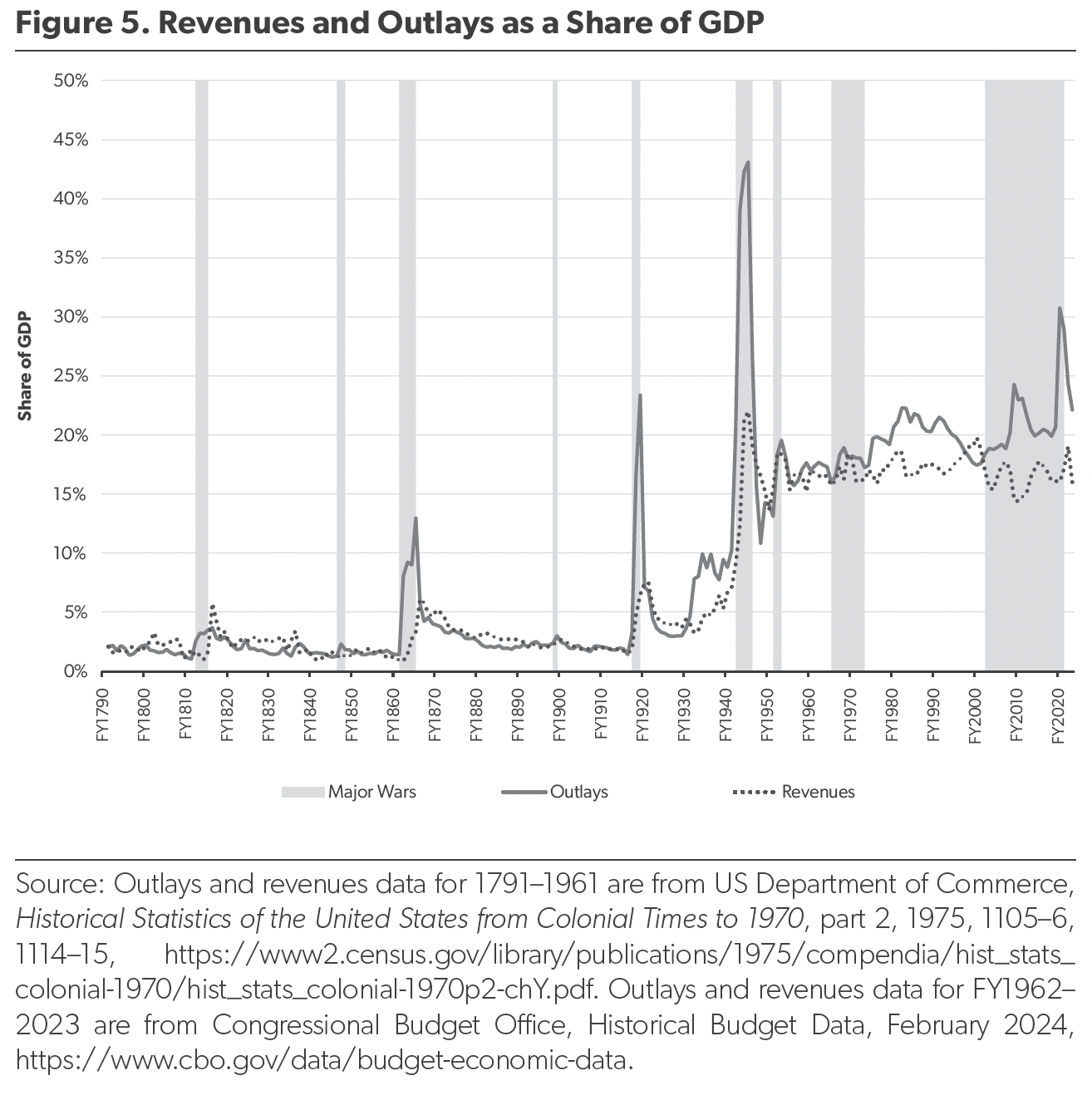

For the United States in its current fiscal condition, the situation is complicated by two additional factors. As shown in Figure 5, total federal outlays as a share of GDP are at a high level by historical standards—they have only been higher during World War II, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Great Recession. Moreover, as outlays have generally trended higher as a share of GDP for the past seven decades, revenues have not grown in proportion. This is an unsustainable trend leading to policy choices that could affect defense spending. Any changes in fiscal policy that widen the deficit, such as tax cuts or increases in nondefense spending, make the situation worse and put long-term downward pressure on the defense budget.

This review of historical data suggests that the current economic burden of defense at 3 percent of GDP is not more than the economy can bear. The nation could spend double what it does on defense without causing serious economic harm, provided it is willing to make the necessary spending and revenue choices to keep the annual deficit at a sustainable level. While the United States has the ability to spend more on defense, it may lack the political will to do so.

Conclusion

Determining how much defense spending is too much is not a simple matter of finding an absolute level that is unaffordable. As this chapter has shown, the affordability and sustainability of defense spending depends more on relative growth rates than on absolute levels. Norman Augustine famously projected in 1967 that if growth in the unit cost of tactical aircraft continued increasing at its current pace, by 2054 the entire defense budget would be needed to procure just one aircraft. His observation was based on simple math: If two trend lines are growing at different rates, the one that is growing faster will eventually overtake the other. When the trend lines are nonlinear, such as compounding growth, the results can be surprising.

A similar set of laws governs the affordability of defense. If the cost per person grows faster than the economy, at some point the nation’s entire GDP will be needed to pay for just one soldier (or, more likely by the time this happens, one guardian). Likewise, if the overall size of the defense budget grows faster than the economy, the defense budget will eventually consume the entire economy. Well before either of these extreme conditions occurs, the nation would begin to encounter serious economic and security consequences. Exactly when those consequences become too much to bear is a matter of politics and risk tolerance.

History suggests that spending as much as 6 percent of GDP on defense can be sustained over time without causing economic harm, but spending more than 10 percent of GDP should be reserved for periods of crisis. A more conservative and forward-looking approach, however, is to monitor the long-term growth rates in defense outlays per person and total defense outlays to ensure the nation stays on a sustainable trajectory and never risks venturing into dangerous fiscal territory during peacetime.

By each of these measures, US defense spending is on a sustainable trajectory with ample room for growth. The economic burden of defense is less than half what it averaged during the Cold War and slightly below the post–Cold War average. Moreover, the cost per person has grown at 2.2 percent above inflation over the past 10 years (excluding costs related to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan), which is below the 2.7 percent growth rate experienced since 1950 and the 3.1 percent growth rate in the economy.20

While the United States spends more than any other nation on defense, this gap is closing quickly as China grows and modernizes its military. Interest payments are projected to exceed defense outlays for the foreseeable future, but both figures remain at a relatively small share of the budget by historical standards. A more concerning trend is that overall federal spending has grown, while revenues have not kept pace. This has led to higher deficits, a larger public debt, and rising interest payments.

Defense spending at its current level is affordable, even if the overall federal budget is on an unsustainable trajectory. The Commission on the National Defense Strategy recommended in 2018 that the defense budget grow at an annual rate of 3–5 percent above inflation, and the commission reiterated this recommendation in its 2022 report.21 While 3 percent real growth should be sustainable, 5 percent real growth could only be sustained for a finite time—a catch-up period. More recently, Senator Roger Wicker, now chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, recommended that the defense budget gradually increase to 5 percent of GDP.22 While this would mean growing the defense budget by roughly 70 percent above its current level, history suggests that the nation would be able to devote 5 percent of its economy to defense indefinitely—provided it makes the necessary choices to raise taxes or reduce other spending. But pegging the budget to an arbitrary share of GDP is the antithesis of strategy.

At current and proposed levels of defense spending, it is not a question of affordability but rather priority. Policymakers must decide if defense should be afforded a higher priority than nondefense programs and activities, and they must be willing to pay for their decisions. Many of the chapters in this book make the case that more resources are needed for defense, and in aggregate these increases are still well within the range of what the nation can afford. This does not mean the nation should increase the defense budget without adequate scrutiny or strategic guidance, nor does it mean the United States should spend more just because it can. How much the nation spends on defense is important, but how the nation spends those precious resources is even more important.

Notes

- See Congressional Budget Office, “10-Year Budget Projections,” https://www.cbo.gov/data/budget-economic-data#3; and Congressional Budget Office, An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024 to 2034, June 18, 2024, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/60039

- Executive Secretary on Basic National Security Policy, A Report to the National Security Council, October 30, 1953, 23, https://irp.fas.org/offdocs/nsc-hst/nsc-162-2.pdf

- Bernard Brodie, Strategy in the Missile Age (RAND Corporation, 1959), 359, 364.

- See Alain C. Enthoven and K. Wayne Smith, How Much Is Enough? Shaping the Defense Program, 1961–1969 (Harper & Row, 1971).

- See, for example, William D. Hartung, More Money, Less Security: Pentagon Spending and Strategy in the Biden Administration, Quincy Institute, June 2023, https://quincyinst.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/17212841/QUINCY-PAPER-NO.-12-HARTUNG.pdf

- Richard K. Betts, Military Readiness: Concepts, Choices, Consequences (Brookings Institution Press, 1995), 5–6.

- Brodie, Strategy in the Missile Age, 358.

- Todd Harrison and Seamus Daniels, Analysis of the FY 2018 Defense Budget, Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 2017, 7–11, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/171208_Defense_Budget_Analysis.pdf

- Jim Garamone, “Dunford Urges Congress to Protect U.S. Competitive Advantage,” DoD News, June 12, 2017, https://www.jcs.mil/Media/News/News-Display/Article/1211862/dunford-urges-congress-to-protect-us-competitive-advantage/

- American Enterprise Institute, “Defense Budget Navigator,” 8, https://defensebudget.aei.org/

- Todd Harrison and Seamus P. Daniels, Analysis of the FY 2019 Defense Budget, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 16–17, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/180917_Harrison_DefenseBudget2019.pdf

- Todd Harrison, Building an Enduring Advantage in the Third Space Age, American Enterprise Institute, May 8, 2024, 26, https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/building-an-enduring-advantage-in-the-third-space-age/

- For example, much of the true inefficiency in the defense budget is due to political constraints placed on the Department of Defense’s ability to close bases, consolidate functions, and retire equipment it no longer needs.

- Samuel H. Williamson, “What Was the U.S. GDP Then?,” MeasuringWorth, 2024, http://www.measuringworth.org/usgdp/

- See Dan Grazier et al., “Current Defense Plans Require Unsustainable Future Spending,” Stimson Center, July 16, 2024, https://www.stimson.org/2024/current-defense-plans-require-unsustainable-future-spending/

- Data are from Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “Military Expenditure by Region in Constant US Dollars,” 2023; and Mackenzie Eaglen, Keeping Up with the Pacing Threat: Unveiling the True Size of Beijing’s Military Spending, American Enterprise Institute, April 29, 2024, https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/keeping-up-with-the-pacing-threat-unveiling-the-true-size-of-beijings-military-spending/

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “Military Expenditure by Region in Constant US Dollars.”

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “Military Expenditure by Region in Constant US Dollars.”

- National defense outlays and active end strength data for 1791–1947 are from US Department of Commerce, Historical Statistics of the United States from Colonial Times to 1970, part 2, 1975, 1114–15, 1141–43, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/1975/compendia/hist_stats_colonial-1970/hist_stats_colonial-1970p2-chY.pdf. National defense outlays and active end strength data for FY1947–2023 are from US Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2025, Table 6-13, Table 7-1, Table 7-5, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/fy25_Green_Book.pdf. GDP data are from Williamson, “What Was the U.S. GDP Then?”

- US Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2025, Table 6-13, Table 7-1, Table 7-5; and Williamson, “What Was the U.S. GDP Then?”

- Jane Harman et al., Commission on the National Defense Strategy, RAND Corporation, July 2024, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/misc/MSA3057-4/RAND_MSA3057-4.pdf

- Roger Wicker, 21st Century Peace Through Strength: A Generational Investment in the U.S. Military, https://www.wicker.senate.gov/services/files/BC957888-0A93-432F-A49E-6202768A9CE0