Defense should not be a priority for the federal government but the priority. Yet America is not spending as much as people think on defense. Meanwhile, taxpayer funds are being wasted by the billions each year under temporary funding measures.

How much can America afford to spend on national security? How do we know how much our security really costs? And how can we get the most bang for our defense buck? To bluntly answer these questions, we need more transparency and predictability in the federal budget than we currently have.

Most Americans support increases in military spending, but as the defense budget approaches $900 billion a year, we should understand our priorities for that budget, what is really in it, and how to get the most from what we spend.1

And we need to start with the basics.

The Declaration of Independence asserts that the government’s first duty is securing the self-evident and unalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. A strong national defense is foundational to all three of these rights. In addition, the United States Constitution makes clear that national defense is the only mandatory function—and exclusively the responsibility—of the national government.2

There are a number of metrics used to evaluate the adequacy of defense spending for America’s needs over time. Some are useful barometers, including defense spending as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), which can help the nation understand how its economic growth and vitality are connected to its spending on security. Some are not useful, such as the ratio of defense spending to nondefense spending, which often accompanies the theory that there should be parity between the two. Federal budgets should reflect national priorities and requirements, not some arbitrary notion of equally divided spending.

The best way to measure the adequacy of the defense budget, however, is not its parity with other costs or its percentage of the GDP but its sufficiency in meeting the military requirements necessary to execute national security and defense strategies and associated missions. On this front, multiple bipartisan commissions have found that the budget—and the defense strategy itself—falls short of what America needs.

For example, according to the most recent assessment of the Commission on the National Defense Strategy, “The threats the United States faces are the most serious and most challenging the nation has encountered since 1945 and include the potential for near-term major war.” Yet the commission found that “in many ways, China is outpacing the United States and has largely negated the U.S. military advantage in the Western Pacific through two decades of focused military investment.”3 (Emphasis in original.) Interestingly, the commission also noted,

The U.S. public are largely unaware of the dangers the United States faces or the costs (financial and otherwise) required to adequately prepare. . . . They have not internalized the costs of the United States losing its position as a world superpower.4

To address resource shortfalls, the commission rightly recommended that Congress immediately provide supplemental funding for a multiyear investment in the national security and innovation industrial bases, focusing particularly on shipbuilding and munitions.

The Strategic Posture Commission made complementary observations regarding the strategic environment, stating,

Today the United States is on the cusp of having not one, but two nuclear peer adversaries, each with ambitions to change the international status quo, by force, if necessary: a situation which the United States did not anticipate and for which it is not prepared.5

In the increasingly violent and chaotic world that these commissions describe, it has never been more important that Americans and their leaders know what the United States defense budget is, how it works, and what it buys. Two key attributes provide the clarity needed to make smart decisions about defense spending and guarantee returns on our security investments: transparency and predictability.

Transparency in the defense budget is inhibited by two things: (1) programs and activities that do not produce military capability and (2) must-pay bills, which give the illusion of flexibility. Both of these affect performance of core functions and fiscal decisions.

Predictability depends on two conditions: (1) the timely passage of annual appropriations and (2) budget agreements that set funding toplines far enough in advance to matter. Without these conditions being met, American military competitiveness is wasted.

The key attributes of transparency and predictability are interrelated, and the challenges that impede them have solutions (Figure 1).

Transparency

Nondefense and Mandatory Spending in the Defense Budget. Budget transparency matters for three key reasons. First, Americans should understand what their security costs and carefully consider the implications of distracting the Pentagon from the missions only it can do. Second, we should be aware of the government-wide reverberations of diverting resources from other agencies’ core missions to defense (known as “mission creep”). And third, if political leaders continue to insist on parity between defense and nondefense spending, we should have accurate data for those discussions and for any spending comparisons between the United States’ spending and that of our allies and adversaries.

Many people know the current Pentagon budget is about $850 billion, so they understandably think that is the cost of the military. It is not. The defense budget is loaded with resources for programs and activities that do nothing to produce military capability. It also contains many annual must-pay bills, which are essentially entitlement spending and mask the real cost of modernizing the military we have into the one we need.

The notion of core functions is crucial to budget transparency. Core functions are the things the Department of Defense (DOD) is expected to do and that only it can do, such as building a Navy, Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, Space Force, and cyber proficiency capable of competing with China; sustaining and modernizing air, maritime, ground, and special operations forces with power-projection competence; and maintaining America’s nuclear capabilities.

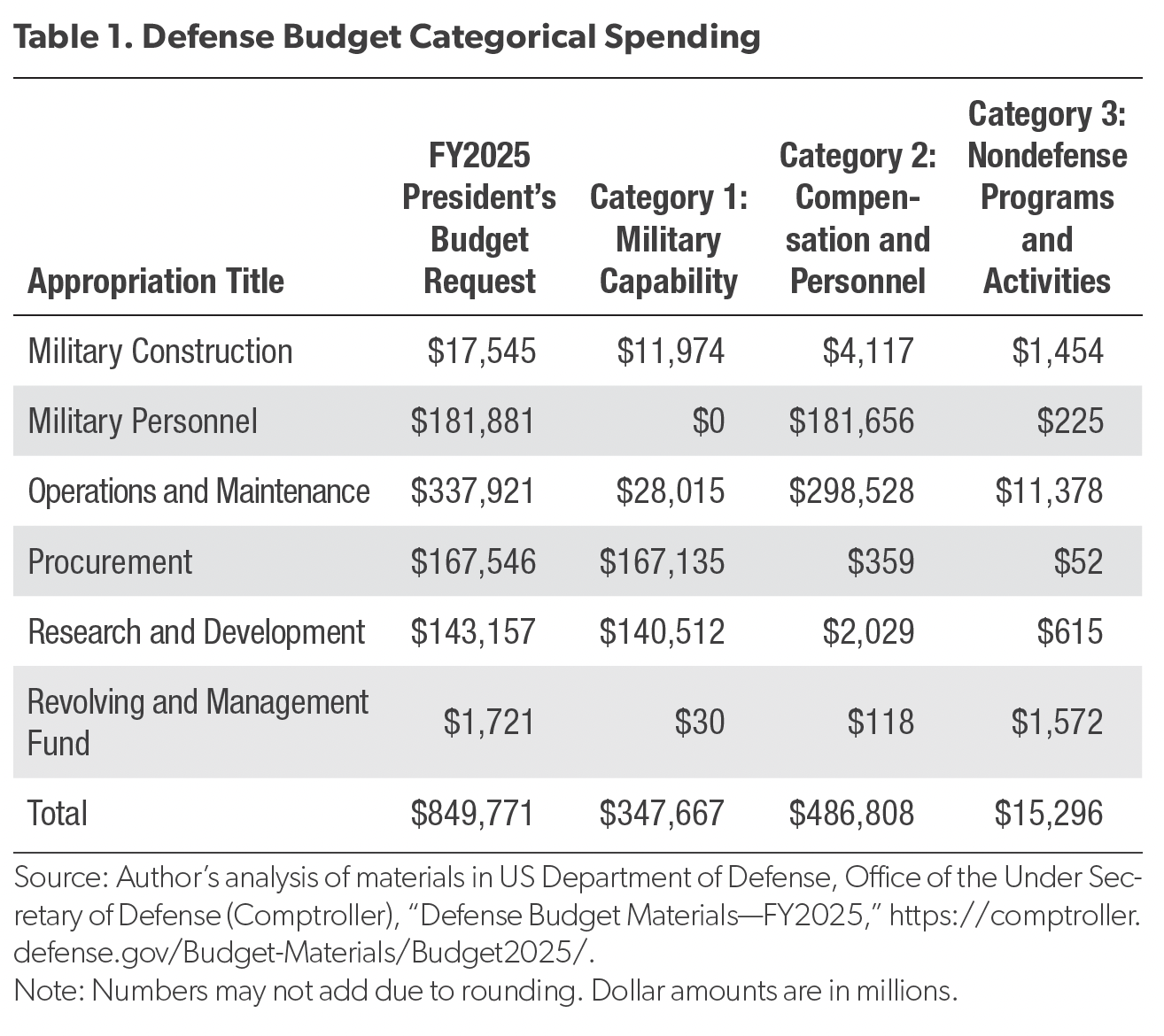

Using a simple methodology to examine the defense budget, Table 1 groups the fiscal year (FY) 2025 request into three categories: (1) military capability and operations, (2) must-pay bills (such as compensation and health care), (3) and missions of other agencies and departments. Even a generous allocation of programs and activities into Category 1 for any efforts that are not clearly defined results in nearly 60 percent of defense spending ($487 billion) falling into Category 2. There, it is consumed by what is essentially mandatory spending, meaning expenses that are tied to previous decisions such as compensation and base operating support, which are not easily changed on an annual basis. More than $15 billion falls into Category 3 and should not be performed by DOD at all. This means that only roughly 40 percent of the annual defense budget is actually discretionary spending that is producing military capability and modernizing the force.

One key reason the military performs so many noncore functions is that the definition of national security has expanded to include numerous other federal responsibilities. Some such activities assigned to the military may seem small in the scheme of the overall budget. Many are worthy efforts. However, they artificially inflate the defense budget and distract from true defense priorities.

A second and related reason is the military’s immense capabilities—particularly in planning, logistics, and emergency response—which lead to an understandable tendency to rely on the armed forces for things beyond their core purpose. When a natural disaster strikes—domestically or internationally—the military is called on to respond. When the southwest border is overrun by those seeking refuge from political persecution or economic hardship—or by criminals trafficking drugs, people, and violence—the National Guard is called to support Customs and Border Protection. When domestic police forces face violent protests, the military may be called for backup.

The military’s exceptional planning and operational capabilities further diffuse its missions. When people seek security, stability, and safety, they look to the military. But the military is a warfighting organization with training and equipment for this mission—not for domestic tasks. Such expansion of the military’s mission brings consequences, financial and otherwise.6 This is particularly true for a military that is already underfunded to meet the expectations of the National Defense Strategy, which is itself outdated.7

Looking closely at Category 3 (Table 2) reveals more than $15 billion in programs and activities that are completely outside the defense mission and should be closely examined for either termination or transferal to a more appropriate agency budget. The entire federal government, including domestic departments and agencies, should contribute to the nation’s security through its assigned missions in homeland security, education, energy, the environment, and health care. Those missions should not be assigned to the Pentagon.

For example, if the nation needs a workforce skilled in engineering, advanced manufacturing, artificial intelligence, and data analytics (and it does), the Department of Education should focus on educating and producing such experts. Yet the Pentagon runs a global school system, educating more than 45,000 students in 106 schools located in 11 countries. These are excellent schools, but running them requires devoting resources to buildings, teachers, and family assistance.

In addition, the defense budget contains set-asides for education research, grants, tuition assistance, and general skill development programs. While these programs may deserve support, they are certainly not a core defense mission. Should funding for them really be considered under defense in budget discussions? And should the Pentagon maintain infrastructure to oversee this activity, thereby distracting it from its primary purpose and the military missions that only the DOD can carry out?

Security assistance, overseas humanitarian disaster and civic aid, foreign economic assistance, and other civil programs are within the purview of the State Department and other civilian agencies. Yet the defense budget has resources for each of these missions—and not just a few million dollars to support the defense contribution to these activities but billions of dollars. These accounts include funding for regional security studies, international legal studies, border security, coalition support, and large investments in security assistance that are typically funded through the State Department as foreign military financing or sales programs. Including funding for these activities in the defense budget artificially inflates the public’s perception of what national security costs, requires manpower to manage them, and pulls resources from the Pentagon’s primary mission.

The Environmental Protection Agency has the specific mission, designated expertise, and accountability for environmental cleanup and restoration, climate change mitigation, and related research. Yet ensconced in the DOD’s operations and maintenance account are environmental restoration programs, each costing hundreds of millions of dollars. Other DOD efforts examine the social science of environmental security and support broad applied research in these areas.8 Again, managing these programs distracts the military from its core function.

Arguably, the military departments should clean up their activities’ environmental effects and contribute to addressing climate change. But the military services are primarily warfighting organizations, charged with developing, deploying, and operating lethal capabilities to protect the nation and its citizens. Though the DOD can and should be a good partner to those charged with these responsibilities, it is important to know how much money is in the budget to lead these efforts.

Note that many of the DOD’s non-mission-critical defense programs and activities that overlap with or duplicate those of other federal departments are funded by defense-wide appropriations accounts. These centralized accounts are not part of the military departments.

Defense-Wide Programs. As efforts are made to save money, reduce redundancy, and improve coordination, the pendulum swings between centralized and decentralized approaches to managing and executing joint functions.

When centralized, shared, or joint functions roll into defense-wide accounts, the accounts are sometimes called the “fourth estate” or—officially—the defense agencies and field activities (DAFA). These defense-wide accounts, totaling $53 billion in operational spending in 2024 alone, are not one thing.9 They are more than 25 different things. Since they involve agencies that are heavily populated by civilian personnel, they tend to be categorized as overhead and targeted for cuts.

But that is a dangerously simple view. These accounts include Special Operations Command, Cyber Command, the Missile Defense Agency, the Defense Logistics Agency, the Defense Contract Management Agency, the Defense Information Systems Agency, and numerous classified accounts. These can’t simply be eliminated. But they can and should be examined to determine what their relevance is to the core military mission, whether centralized management still makes sense, and whether the required functions are best performed by the government at all.

For example, hidden in DAFA is an annual appropriation of close to $1.6 billion for commissaries.10 Tracing their history back to 1825, the commissaries—now run by the Defense Commissary Agency—were set up to provide convenience and support to military families in austere locations. Now seen as an earned benefit for military members, their families, and veterans, the commissaries should deliver the best possible service and savings to patrons while maintaining budget-neutral operations for the taxpayer.11

But according to numerous reviews, studies, and assessments over the past decade, the commissaries are falling short and costing more. While the cost to the taxpayer rises, performance and utility steadily decline.12 Yet the Pentagon has been unwilling to even fairly test alternative management structures. This is a prime example of a taxpayer-funded, noncore military activity that provides subpar service to deserving Americans and that could—and should—be better run to provide improved service in a self-sustaining manner.

In another instance, the National Institutes of Health is charged with performing fundamental research to improve health and reduce illness, so it leads basic and applied medical research on cancer and autism, among other things. Yet DOD also spends billions each year on these efforts. For example, the $40 billion Defense Health Program (DHP) provides medical and dental services to active forces and other eligible populations while training medical personnel. The DHP includes $900 million for research to address some military—but many nonmilitary—challenges. The DHP’s budget request includes almost $63 million for research on breast cancer, gynecological cancer, and similar nondefense efforts, which would be more appropriately funded by other agencies whose mission is to tackle these challenges.13

Moreover, Congress routinely adds billions in nondefense spending to the budget—money that, in a zero-sum fiscal situation, often comes from the accounts the Pentagon uses to buy weapons or sustain force readiness. For example, every year, over $1 billion is added for medical research, $85 million for various education programs and grants, $50 million for the National Guard Youth Challenge Program, $53 million for DOD Starbase (a STEM education program for grade school children), and $25 million for natural resource management.14 These efforts may be worthwhile, but it would be hard to argue that this spending is more important to military capability than addressing the numerous warfighting shortfalls in unfunded priorities that the nation’s senior military leaders list each year.

Assigning all these responsibilities to DOD inflates perceptions of the nation’s security spending and diverts attention from military capabilities. Every time a new mission is assigned to DOD, it must manage, plan, execute, assess, and report on the activity. This draws time and resources from the core defense mission: preparing for, fighting, and winning America’s wars.

It remains crucial for agencies with complementary missions—such as the Departments of Defense, Energy, Homeland Security, and State—to work closely together. And though some of these separate missions and agencies could arguably be consolidated, this should not be done by putting the budget for one agency with distinct responsibilities—and accountabilities—into another agency’s budget and organizational structure.

There is also a second-order corrosive effect of deferring to defense planning, management, and response expertise. Assigning nondefense missions to the Pentagon has ramifications for civilian-military relations. As the military is asked to perform nonmilitary activities, the lines between military and civilian roles and responsibilities blur, which risks damaging the military’s historical, appropriate place in society as the nation’s warfighting force.

Making Spending on Military Capability More Transparent. Solving the defense budget transparency and misalignment problems is straightforward, involving two basic steps. But it is not easy, as it will require cooperation by DOD, the Office of Management and Budget, and Congress.

First, we need to clear out the noncore-mission programs and activities that have complicated the budget structure and pulled resources and attention from core defense programs. We should align environmental, energy, education, security assistance, and civilian medical research programs with their relevant organizations. If such programs are deemed lower priority, we should terminate them, at least at the federal level. If, like the commissaries, they can be better run while improving service, we should not hesitate to test and make changes. We should then move entitlement-like spending that is embedded in the defense budget—for things like health care, compensation and benefits, military and civilian pay, and operational support—to a separate mandatory budget for management and execution.15

Once those two things are done (which, with sufficient support, could be accomplished in a few budget cycles), we will have a clearer picture of the $348 billion in actual defense discretionary spending. We should then restructure the budget to support the most effective program management and to easily—and automatically—answer key management and oversight questions. This effort falls under budget reform and will be easier once the first two steps are taken.

Even the most productive and successful defense budgeting modernization effort for speed, agility, responsiveness, and transparency won’t matter without budget agreements that enable timely enactment of annual appropriations. This brings us to the second main attribute necessary for getting the most out of each defense dollar—predictability.

Predictability

The Waste and Consequences of Delayed Funding and Unpredictable Budgets. The second key driver of defense budgeting waste and confusion is the dual failure of the annual federal budget and appropriations processes.

In 2011, the country was faced with such increasingly high deficits (some of which were created by these processes) that, under the Budget Control Act, the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction was formed to fix it. As an incentive, the act specified that if the commission failed to reduce the deficit, draconian and arbitrary cuts known as “sequestration” would be made.

No one expected the commission to fail, but it did, and in January 2013, sequestration began. Starting in December 2013, Congress reached a series of two-year bipartisan budget agreements to set funding caps above the Budget Control Act’s limits. These agreements demonstrated that setting discretionary budget caps in advance of the budget year is actually possible. Such multiyear budget agreements should happen regularly to establish discretionary funding targets without incurring damage like that caused by the Budget Control Act, from which defense readiness and modernization are still recovering today.

Continuing Resolutions. The second and related key expression of federal fiscal failure is the annual appropriations process. When Congress fails to pass 12 separate pieces of funding legislation, it resorts to temporary stopgap funding measures known as continuing resolutions (CRs), which extend the previous year’s funding and priorities into the new fiscal year and restrict new spending. Otherwise, the federal government experiences a lapse in appropriations and shuts down.

The consequences of delayed funding and CRs can be dire—including significant and unnecessary costs to taxpayers, lost lives, poor living conditions for United States service members, and delayed contracts necessary to procure and manufacture the defense equipment and technology we need.

The nation has lost five of the past 15 years to avoidable and wasteful CRs.16 During this time, defense programs, activities, contracts, innovation, and personnel have stagnated when the nation could—and should—have been advancing military competitiveness. Without funding for new priorities, the Pentagon must incrementally fund what it needs, driving up the costs of goods and services and burning time we can’t afford to lose. In fact, the taxpayer has lost nearly $68 billion in buying power under CRs in the past two years alone. This does not include the increased costs of incrementally funding contracts or the widespread impact on anyone who works on or for military bases across the country.17

In 2023 alone, 33 service members were killed in training-related accidents. Nine soldiers perished when two HH-60 Black Hawk helicopters crashed during a nighttime training accident in Kentucky.18 Eight Air Force special operators were killed in a CV-22 Osprey crash in Japan during a training mission.19 Similar stories account for the other deaths during air refueling, parachute, and other training missions.20

Military training accidents can have many causes, but it is clear that delayed and unpredictable funding disrupts training schedules and, as a result, affects the safety of our service members. Consistent training and meticulous care of equipment are cornerstones of an effective, professional, and safe military. These standards are more difficult to uphold when funding is uncertain or indefinitely delayed.

Further piling onto the avoidable problems attributed to budgetary unpredictability is the impact on the maintenance of facilities where our uniformed personnel live and work. The restrictions on new funding under CRs mean that no new military construction projects are awarded until regular appropriations are enacted. This affects family housing, which is already widely known to have many serious problems, including safety risks, sewage overflows, inoperable fire systems, broken windows, bug infestations, cold showers, inadequate heating or cooling, and mold. The Pentagon is trying to make improvements, but insufficient, inconsistent, delayed funding for this fundamental and fixable need undermines force readiness, harming America’s security.

The impacts of budget uncertainty and delays in annual appropriations cascade into the industrial base and supply chain, since unpredictable—or missing—demand signals and incremental contracting result in acquisition strategies that must hedge against various budget topline scenarios. Alliances and partnerships also suffer from budget uncertainty, which delays exercises and forces foreign militaries to hedge their bets on sales we may be unable to fulfill on time. Without annual funding, the Pentagon can’t award contracts. As a result, industry, the workforce, and the supply chain wait, and the health and resilience of the entire system withers. Meanwhile, America’s military equipment ages, becoming more expensive to maintain.

A CR’s customary resolution is an omnibus appropriations bill covering all (or large portions of) federal spending. Such legislation—which typically contains thousands of pages and awards trillions of dollars of funding—forces members of Congress to vote with little knowledge of its contents. This leaves the public largely in the dark as to how national security is funded and what it costs.

It is hard to imagine a way to inflict more expensive, avoidable harm to the American economy and military competitiveness than what we see each year during the annual appropriations process. Imagine running a race and spending one-third of it looking for your shoes. What are your chances of winning?

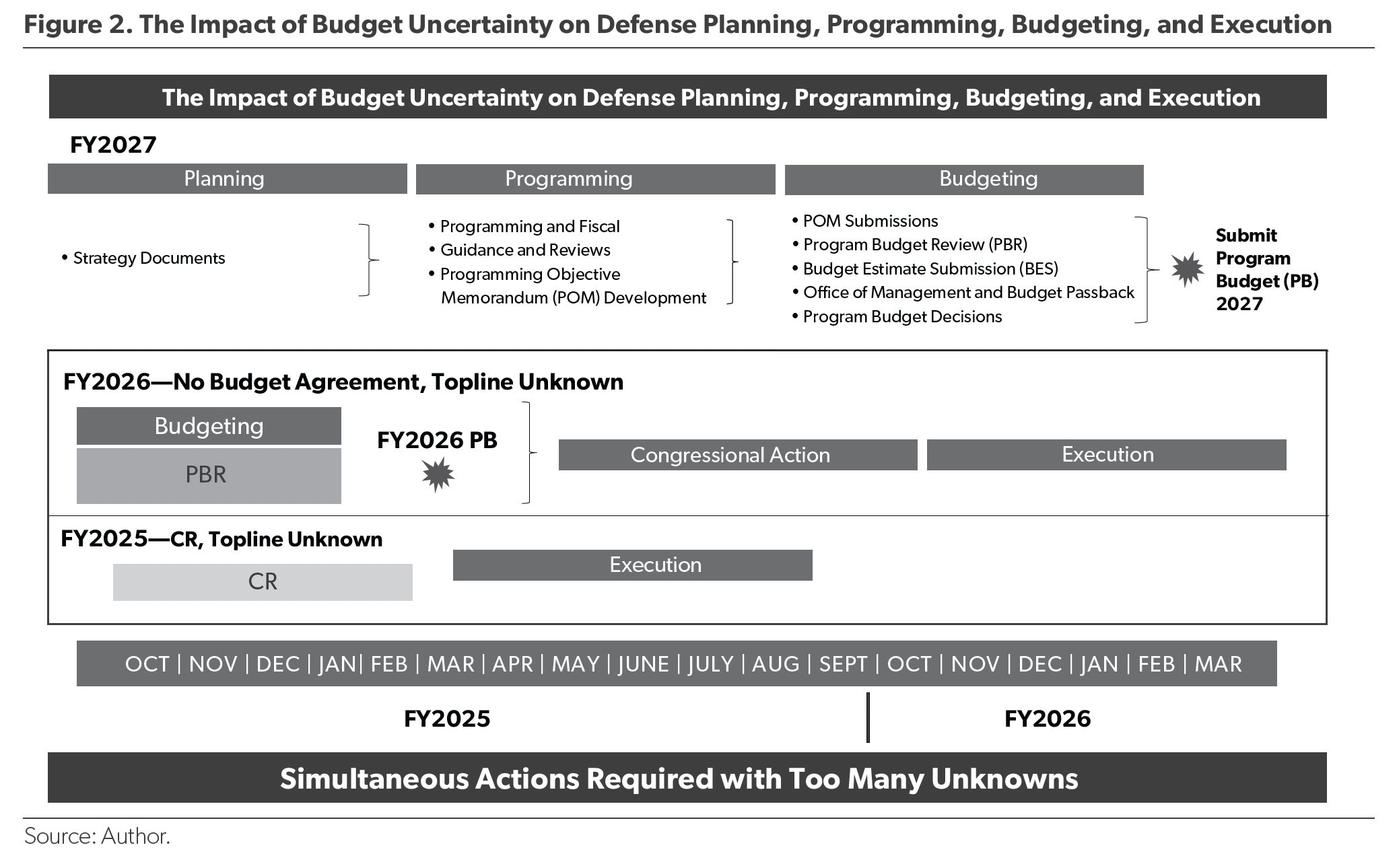

Budget Agreements and Defense Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution. Planning and programming without a budget often result in strategy-resource mismatches and contingency planning, which waste time and inhibit good decision-making.

In turning strategic direction into military capability, the military starts planning and programming years before the budget request is actually submitted to Congress. This advance planning is necessary, but it would be more effective if budget agreements set topline discretionary funding levels, even if those caps are modified during the process. Instead, when the DOD begins planning its budget, it often faces three years of uncertainty before the budget even reaches Congress. For example, as the Pentagon plans programs that will be in the FY2027 budget request, it is operating under a CR for FY2025 and is in the budgeting phase of programs for FY2026, which has an unknown topline (Figure 2). This makes such planning a shot in the dark at a near-fictional budget future.

This mismatch leads to numerous hedging and contingency strategies in budgeting and acquisition that spread uncertainty, and therefore inefficiency, throughout the system. Innovation, manufacturing, construction, and even education and training are all subject to best-guess planning, which increases costs and reduces responsiveness. If we wonder why the federal government—and the Pentagon in particular—can’t make smarter decisions, this is a key reason. Consistent, predictable budget agreements and funding would yield more informed decision-making and better contract negotiations.

Budgeting—particularly any Future Years Defense Program projections that the Pentagon is required to produce—is also inhibited by delayed annual funding and general budget uncertainty. For example, it is now common for agencies to operate under temporary funding measures, as mentioned above, while making decisions for the next budget year and building programs for the next five years. Programs are unlikely to be executed as envisioned while they wait for defense appropriations, yet the ability to execute them is being used to evaluate program performance and inform future budget estimates.

The Pentagon cannot get the best deals if it does not know how much it will be buying or even whether Congress will approve what it proposes to buy. Acquisition strategies rely on contracts that are unlikely to even be awarded within the first two quarters of the fiscal year (thanks to CRs). As a result, opportunities for accelerating innovation are lost, the technological “valley of death” between developing and implementing promising solutions to evolving military problems—like counter-drone warfare—widens, and the department is forced into incrementally funded, year-by-year procurement deals. This inflates unit costs due to uncertain or truncated orders, which is not exactly a recipe for a good return on what should be strong buying power.

In the end, the self-inflicted wound of uncertain and delayed budgets results in a less ready, less modern, and less resilient force; a more vulnerable and costly industrial base; and a public that does not have the visibility and security it deserves. All this is funded by a budget loaded with tangential missions and must-pay bills that are financed in the least cost-efficient manner.

Fixing the Budget Uncertainty Problem. Similar to improving budget transparency and responsiveness, solving the budget uncertainty problem to get the best return on the defense investment requires close partnership with—and action from—Congress.

To support effective planning by defense program and budget experts and the industrial base, we must know what the budget is, and it must be enacted on time. This requires the right incentives in the right places.

The penalty for not reaching budget agreements or passing annual appropriations on time should be directed at those with the power to make the change and the responsibility to do so. Our elected officials seem to recognize the importance of regularly developing and approving annual government spending legislation. For instance, the Fiscal Responsibility Act, which was enacted in 2023 to raise the debt limit and set budget caps for 2024 and 2025, included a penalty for failing to enact regular appropriations bills by the start of the calendar year.21 But though this nod to the importance of finishing work on time was admirable, it did not prove valuable. In fact, the penalty for failure—further reductions to an already insufficient defense budget—was imposed on the nation’s security and not on the elected officials in a position to do something about it.22

However, creating penalties and incentives was the right tactic. If Congress agrees it should avoid CRs, it should make governing this way so toxic that it stops happening. There are three complementary ways to get serious about this approach.

First, suggestions that Congress should not pay itself if it does not perform its fundamental duty on time have been ignored. But they are key to breaking the current pattern. Congressional pay should be linked to completing appropriations on time. For each week of delay after the start of the fiscal year, Congress should impose a 10 percent pay cut on itself until it enacts final appropriations.

Second, term limits should be linked to job performance—meaning accomplishing the fundamental duty of passing annual federal funding legislation on time each year. One way to do this is to connect running for reelection to some minimum successful outcome on behalf of the American taxpayer. Elected representatives and senators should agree that if they miss budget deadlines in any three years of a six-year cycle, they will not run for office in the next election.

Third, after the new fiscal year starts on October 1, if annual appropriations are not done, then all other congressional priorities should halt until they are. Congress could include this directive in a budget reconciliation measure—making clear that until annual appropriations are enacted, there will be no action on other legislation. During this time, the DOD will not be required to submit any congressional reports or provide witnesses for hearings. And no government-supported congressional or senior leader travel will be conducted.

Implementing these three incentives would clarify the importance of Congress fulfilling its most fundamental job on time, involve every member of Congress (not just those in leadership or on appropriations committees), and save taxpayers billions that is lost annually under CRs.

Conclusion

Solving the lack of budget transparency and predictability that obscure the affordability of American national security and waste money require fearless leadership and close partnership among the Pentagon, the White House, and Congress to prioritize America’s defense.

Transparency and predictability can save money and improve Americans’ understanding of what our military costs. To achieve these two interconnected attributes, policymakers should take four actions. First, stop loading the defense budget with items that do not produce military capability. Second, treat must-pay defense bills as what they are, mandatory spending. Third, de-link defense spending from nonsensical discussions about parity, and routinely and consistently pass budget agreements that set discretionary spending toplines. Fourth, create tangible incentives and penalties for causing uncertain and delayed budgets, thus eliminating huge, delayed omnibus spending measures. In summary, put America’s security first, and get the best price for what the country buys.

Notes

- Beacon Research, “US National Survey of Foreign Policy Attitudes on Behalf of the Ronald Reagan Institute,” November 14, 2024, https://www.reaganfoundation.org/reagan-institute/centers/freedom-democracy/survey/reagan-institute-summer-survey-2024

- US Const. art. IV, § 4; and US Const. art. I, § 10.

- Jane Harman et al., Commission on the National Defense Strategy, RAND Corporation, July 29, 2024, v, https://www.rand.org/nsrd/projects/NDS-commission.html

- Harman et al., Commission on the National Defense Strategy, viii.

- Madelyn R. Creedon et al., America’s Strategic Posture: The Final Report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, Institute for Defense Analyses, October 2023, v, https://www.ida.org/research-and-publications/publications/all/a/am/americas-strategic-posture

- Elaine McCusker, “The Potential National Security Consequences of Unplanned Domestic Military Missions,” Lawfare, September 26, 2024, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/the-potential-national-security-consequences-of-unplanned-domestic-military-missions

- Elaine McCusker, “2025 Defense Budget Request—Substance v. Spin,” AEIdeas, March 12, 2024, https://www.aei.org/foreign-and-defense-policy/2025-defense-budget-request-substance-v-spin/; and US Department of Defense, 2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America, October 27, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF

- US Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), “Defense Wide Budget Documentation—FY2025,” https://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials/Budget2025/

- US Department of Defense, Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), Department of Defense Operation and Maintenance, Defense-Wide Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 Budget Estimates: Summary by Agency, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/budget_justification/pdfs/01_Operation_and_Maintenance/O_M_VOL_1_PART_1/Summary_by_Agency_(Part_1).pdf

- US Department of Defense, Defense Commissary Agency, Operating and Capital Budget: Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 Budget Estimates, February 2024, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/budget_justification/pdfs/06_Defense_Working_Capital_Fund/DeCA_PB25_J-Book.pdf

- Elaine McCusker, “Should Military Commissaries Be Privatized? Yes . . . ,” Ripon Forum, November 2024, https://www.aei.org/op-eds/appreciating-servicemembers-and-veterans-through-a-better-commissary-benefit/

- Elaine McCusker, “It’s Past Time to Unleash the Defense Commissaries,” Military Times, July 26, 2023, https://www.militarytimes.com/opinion/2023/07/26/its-past-time-to-unleash-the-defense-commissaries/

- US Department of Defense, Office of Prepublication and Security Review, Defense Health Program: Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 President’s Budget, Operation and Maintenance Procurement, Research, Development, Test and Evaluation, March 2024, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/budget_justification/pdfs/09_Defense_Health_Program/00-DHP_Vols_I_and_II_PB25.pdf

- H.R. 9747, 118th Cong. (2025).

- Mackenzie Eaglen, “For Better Defense Spending, Split the Pentagon’s Budget into Two,” The Hill, February 15, 2023, https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/3859140-for-better-defense-spending-split-the-pentagons-budget-into-two/

- Elaine McCusker, “Are We Paying for Performance,” AEIdeas, September 24, 2024, https://www.aei.org/foreign-and-defense-policy/are-we-paying-for-performance/

- Elaine McCusker, 2024 Continuing Resolution: Defense Losing $300 Million per Day in Buying Power, American Enterprise Institute, January 25, 2024, https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/McCusker-Buying-Power-One-Pager-Final.pdf

- Sharon Johnson et al., “9 Killed in Army Black Hawk Helicopter Crash in Kentucky,” Associated Press, March 30, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/us-military-helicopters-crash-kentucky-89c9dbcd035b3cc7c637c2b1f0a037a2

- Courtney Mabeus-Brown, “Air Force Ends Effort to Recover Final Member of Downed Osprey’s Crew,” Air Force Times, January 11, 2024, https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2024/01/12/air-force-ends-effort-to-recover-final-member-of-downed-ospreys-crew/

- Lolita C. Baldor, “US Military Aircraft Crashes over Eastern Mediterranean Sea,” Associated Press, November 11, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/military-aircraft-crash-mediterranean-50b45d9fc4956ede96076a7d21f42eb4; Gidget Fuentes, “Parachuting Accident Claims Life of Navy SEAL,” US Naval Institute, February 22, 2023, https://news.usni.org/2023/02/22/parachuting-accident-claims-life-of-navy-seal; Jessica Edwards and Davis Winkie, “Three Dead After Two Apache Helicopters Collide in Alaska,” Army Times, April 27, 2023, https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2023/04/28/two-apache-helicopters-crash-in-alaska/; and US Marine Corps, “15th MEU Identifies Marine Killed in Rollover at Camp Pendleton,” press release, December 14, 2023, https://www.15thmeu.marines.mil/News/Press-Releases/Announcement/Article/3617925/15th-meu-identifies-marine-killed-in-rollover-at-camp-pendleton/

- Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, Pub. L. No. 118-5.

- Elaine McCusker and John G. Ferrari, “Budget Endgame Scenarios: From Acceptable to Apocalypse,” Breaking Defense, August 28, 2023, https://breakingdefense.com/2023/08/budget-endgame-scenarios-from-acceptable-to-apocalypse/